An impeccable, concise report on seven years of fieldwork at the town of Interamna Lirenas, this book gives one of the clearest examples so far of the extraordinary wealth of detail that ground-penetrating radar (GPR) provides for ancient sites. What is mapped and analysed here represents perhaps 75% of the town, missing only those areas on the lower slopes where the colluvial deposits masked the remains. Combined with a well-analyzed surface survey of the pottery, and the evidence from epigraphy, the sources and a very little excavation, the new plan allows the authors to write a fairly comprehensive biography of the town, and to expand from this into the information it provides for small towns elsewhere in central Italy, and, in particular, the Latin colonies. The dynamics of its development can be minutely reconstructed from the plan, even though stratigraphy is largely missing, because of the relationship between the buildings and the original road network.

As with many new towns, an existing road—in this case the Via Latina—formed the backbone of the site, which occupies a rather narrow ridge between two tributaries of the Liri at a point where it is crossed by secondary roads linked to the Via Appia to the south and to Casinum to the northeast, along a probable transhumant route that led on into the Apennines. Founded as a Latin colony in 312 BC, it forms part of the group of Latin colonies intended to reinforce the valley of the Sacco-Liri against the Samnites. Livy (9.28.8) tells us that it had 4000 (male) colonists. The site had been previously investigated by Cagiano de Azevedo in 1947 and by the Liri survey of McMaster University, tragically aborted by the murder of one of its directors, Edith Mary Wightman, in 1983.[1] The two studies agreed that the apex of the town’s prosperity was to be found in the late Republic, and that it had entered a slow decline after Augustus.

The first three chapters introduce the town, the project and its methodology. This shows the shift in geophysical prospection methodology over the past two decades. A fluxgate gradiometer survey carried out by Sophie Hay of the British School at Rome was combined with surface survey of the site. While showing the main lines of the settlement, it was felt not to be detailed enough, so a second survey was carried out with GPR. This gave quite astonishingly clear results: not only walls and roads but even porticoes and doorways stand out in the very detailed plans of the insulae that form chapter 4. Here ten plans at 1:1000 show the areas of the city, with the insulae mapped and the buildings numbered. A short text describes each insula, commenting on specific, numbered, buildings that are distinguished by colour on the plans. They then move from the specifics of the individual insulae to the distribution and chronology of the pottery collected on the site, with periods divided into 150-year units. The forum is central for all periods, but during the initial century and a half settlement in the colony seems to have been limited to its immediate area. By the second century, though, settlement had expanded throughout the colony, and continued dense through the middle of the third century AD. At this point, however, it began to shrink back towards the central, forum, area. The survey is not, of course, entirely reliable, in that the lower slopes produced far less pottery, as the colluvium from deep ploughing has probably made most surface pottery inaccessible. Still, though the datable sherds were few, the results are consistent.

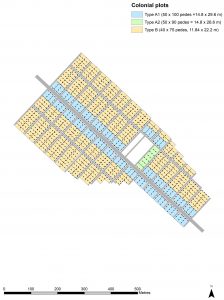

The fifth chapter constitutes the heart of the book, in which the original plan of the colony is deduced from the vagaries of the reconstructions, consolidations and encroachments recorded by the survey. The Via Latina forms the spine, flanked by two parallel, secondary roads. The town is divided into perpendicular, oblong, insulae by streets at regular intervals of160 Roman Feet (RF), or 47m. The exception is the elongated forum, perpendicular to the Via Latina in the centre of town, and flanked by two half-sized blocks of buildings: with these, it occupies the space of two insulae. The authors then produce the plausible hypothesis that the original plan involved two sizes of house plot: those fronting onto the Via Latina, measuring 14.6 x 29.6 m., or roughly 50 x 100 RF, and those fronting the side streets, measuring 11.84 x 22.2, or 40 x 75 RF (fig. 1). An exception is found in the forum, along whose southeast side lie seven houses. These compensate for their exalted position on the forum by being 10 RF shorter than the ones along the Via Latina. This scheme, of course, beautifully complements the pattern of differential housing for equites and pedites I identified for the resettlement of Cosa in the early second century,[2] but pushes it back over a century into the Middle Republic. The authors point out that a classis system based on a military hierarchy is unsurprising in this period. Like those at Cosa, the houses on the forum and along the principal artery constitute the dwellings of a ready-made class of decurions.[3] The original buildings on the other side of the forum are hard to identify: a circular comitium is proposed for the middle of its northwest side, but without supporting geophysical evidence, or any trace of a curia. All of the other structures are apparently later.

The authors then calculate the population of the town from the 500-odd houses, coming to a figure that rounds to around 2000. This immediately demonstrates that the bulk of the 4000 male colonists and their families– some 3,500 of them—would have built their houses on their allotments in the newly-centuriated ager. Those settling in the countryside would have included over 200 of the equites, probably on larger plots, as there was room for only 91 of the perhaps 300 of these within the colony. Indeed, the limited nature of the settlement of the third century leaves the question open as to whether all the predestined plots were taken up initially. What we seem to see here, as in the case of Carthage, is a plan that was neatly laid out, but remained a skeleton at its extremities.

By the second century, however, the plan had filled out, and new public buildings began to emerge: a temple, basilica and a possible carcer on the forum, and, just to the north of it and across the street from the basilica, an elegant, covered theatre built in the Augustan period, dripping with coloured marble. New sanctuaries were created on the southwest edge of the town, facing the valley and visible from afar. Courtyard buildings, particularly at the northwest, may have been artisanal spaces or horrea, while a large empty space at the southeast end of town is identified as a forum pecuarium. It seems possible that this was also the site of the nundinae, an idea that is reinforced by the buildings on the insula immediately adjacent to it, which seem to include a tholos and an aedes, essential structures that sanctified and guaranteed market transactions.[4] But the vast majority of the town’s buildings were domestic in nature: it remained an agro town, with very little evidence for non-agricultural productive activity. Indeed, there is very limited evidence for imported pottery of any sort, African Red Slip or even amphorae, which tends to suggest that the town’s own production for wider markets was limited. However, Interamna occurs on two overlapping schedules for nundinae, which suggests a role in the regional economy (Inscriptiones Italiae 13.2.49-50). What was it producing? A possibility that the authors largely overlook would be textiles, using the wool from the transhumant flocks and weaving it into cloth for the regional market, perhaps in an intensive fashion within the courtyard buildings, or simply within the houses themselves.

The mid-third century saw the abandonment of the edges of the town, which shrank back towards its centre. However, its impressive bath building was restored on two separate occasions, the second in the early fifth century. The theatre, too, appears to have been in use through the fourth century. The town clearly served as a pole for social interaction and local government, and perhaps an important way station for the Via Latina, until the Lombard invasion of 568 sealed its fate. The later castle of Teramen was created after an abandonment of at least three centuries.

In their conclusion, the authors return firmly to the traditional idea that the colonial centres were planned as the urban centres of city-states. The original settlers were destined for both the planned town and its measured countryside, the forum the centre of a quasi-autonomous political entity, with clear boundaries. But its apparent prosperity through into the third century is less usual for towns in central Italy: Cosa was more or less dead by the reign of Hadrian, as were numerous other towns closer to Rome (although some, like Falerii Novi, seem to have experienced a Late Antique revival).

The results of the GPR, in combination with the surface survey, speak for themselves. Equally staggering plans are now emerging for Falerii Novi.[5] This is a technique that is fast becoming indispensable, especially given what we now know to be the limits of magnetometry. The book gives us a clear and cogent account of the history of a (perhaps unexceptional) Latin colony. My only quarrel with it is that, in publishing only their work on the town, they are ignoring their survey of the countryside, which is barely mentioned. The survey has appeared in an article,[6] but it certainly belonged here, if only to show how the dynamics of settlement in the ager reflected—or did not—those in the town. I hope it will be the subject of an integrated companion volume.

Notes

[1] M. Cagiano de Azevedo 1947, Interamna Lirensas vel Sucasina (Italia Romana: Municip e Colonie II.2). Rome, Istituto di Studi Romani Edizioni; J. Hayes and I. P. Martini, eds., 1994, Archaeological Survey in the Lower Liri Valley, Central Italy (BAR International Series 595). Oxford, Tempus Reparatum, 127-158.

[2] E. Fentress, 2003. ‘Cosa in the Republic and Early Empire’ in E. Fentress, Cosa V: An Intermittent Town (MAAR Supp. 11) Michigan University Press, Ann Arbor, 13-62.

[3] I might note that the suggestion that the Cosa housing pattern also dates to its first foundation, in 273 BC, runs up against the problem that the houses on the forum are built into a cut in bedrock, and the earliest contexts at the bottom of the cut can be no earlier than the 170s.

[4] E. Fentress, 2007. ‘Where were North African Nundinae held?’ in C. Gosden, H. Hamerow, P. de Jersey and G. Lock, edd. Communities and Connections: Essays in Honour of Barry Cunliffe. Oxford University Press. 125-141. It would be very interesting to excavate a sample of the open space.

[5] L. Verdonck, A. Launaro, F. Vermeulen and M. Millett 2020. ‘Ground-penetrating radar survey at Falerii Novi: a new approach to the study of Roman cities.’ Antiquity 94 (375): 705-723.

[6] Launaro, A. 2019. ‘Interamna Lirenas—a history of ‘success’? Long-term trajectories across town and countryside (4th c. BC to 5th c. AD). In A. Di Giorgi (ed.) Cosa and the Colonial Landscape of Republican Italy (Third and Second Century BC) Michigan University Press, Ann Arbor, 119-38.