Fulvia: Playing for power at the end of the Roman Republic, by Celia E. Schultz, is a timely addition to the Women in Antiquity series published by Oxford University Press. As stated in the presentation, the series, which “selects figures from the earliest of times to late antiquity”, amounts so far to 18 monographs on individual women from ancient times. Fulvia is given her place among other women of the first century BCE, such as Cleopatra, Clodia Metelli and the so-called “Turia”. Although one of the objectives of the series is to provide “compact and accessible introductions”, the book’s 130 pages, including bibliography and indices, go to show the relatively thin knowledge that we have of Fulvia (and even of other women of the period). Even so, there is much to be said about her.

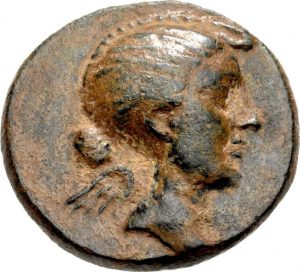

Throughout the book, Schultz has been careful to note that there are many things that we do not know about Fulvia, such as what she looked like. As is the case with many other women of the late Republic, and even her first husband Clodius, there are no images of her. The coinage struck at the Roman mint in Lugdunum by Antony in the late 40s, together with a coin from the city of Eumeneia in Phrygia, features a female head in profile, usually identified as the goddess Victory, but sporting the typical hairstyle of first-century-BCE matrons. Since the nineteenth century, some scholars have suggested that the goddess has Fulvia’s features, although opinions are divided and Schultz is sceptical on this point.

There is much more to Fulvia than first meets the eye, as Schultz analyses throughout her book. She belonged to the gens Fulvia, a family originally from Tusculum. Her mother was Sempronia, who might or might not have been the Sempronia who collaborated in the Catilinarian conspiracy, as Schultz discusses (pp. 12-13). As a very young woman, Fulvia married the future tribune Publius Clodius, probably one of the most important politicians of the 50s and a popularis leader who managed to exile Cicero. After the murder of her husband, Fulvia married Scribonius Curio, another rising politician who died in Africa during the civil war. Her third and last marriage was to Mark Antony, magister equitum, consul, triumvir and, ultimately, Octavian/ Augustus’ great adversary.

Her family connections by marriage are certainly impressive. However, she should not only be considered as “the wife of”, for which reason Schultz performs an in-depth enquiry into her life and public acts. When Clodius was murdered by his enemy Milo on the Appian way, Fulvia was instrumental in eliciting a powerful reaction from the people by weeping in public and immediately allowing them to view the body, bloodied and displaying all the inflicted wounds. The following day, during the funeral, the crowd built a pyre in the forum, which subsequently burned down the Curia. More importantly, she was one of the visible heads of the Perusine War (41-40 BCE), in which the triumvir Octavian confronted the consul Lucius Antonius, Fulvia’s brother-in-law (and Antony’s brother). In both cases, Schultz is careful to qualify her role; her death in 40 BCE allowed for the reconciliation between Antony and Octavian and converted her into a scapegoat, “pinning responsibility from the bloodiest and most embarrassing episodes of his period on her” (p. 74). However, recovered slingshots from the siege of Perusia, inscribed with sexual insults aimed at her, suggest that she played a certain role in the revolt, or she was at least cast into this role by Octavian’s propaganda. In sum, Schultz defines her as a person of real political acuity who not only staunchly defended her husbands’ interests, but also behaved like a proper materfamilias and served as a role model for subsequent strong-minded imperial women.

There is a thread that traverses the whole book: on several occasions, Schultz observes that the accounts of Fulvia in the sources belong to hostile narratives towards her husbands. In this respect, she frequently recalls that our knowledge of Fulvia is “the product of the imagination of her husband’s enemies” (p. 2). As Cicero was an arch-enemy of both Clodius and Antony, his account probably influenced subsequent approaches to her figure, such as that taken by the historian Cassius Dio, one of the authors who cast her in a very unfavourable light. This can be clearly seen in the contrast between her actions and those of Octavia, Antony’s fourth wife and Octavian’s sister: both Fulvia and Octavia recruited troops, but, while the latter is lauded in the sources for displaying devotion towards her husband, the former is accused of having transgressed all matronly norms (p. 101). These considerations are relevant and should be borne in mind in any study of women in Antiquity.

Schultz’s narrative is pacey, engaging and very coherent: in sum, a delight for readers. I attempted to read the book as if I were a student or a specialist in other periods of history and, by my reckoning, Schultz has been successful in this sense. She has been able to explain very clearly the dynamics of Roman politics and the high stakes in the civil war, providing all the relevant sources in footnotes, while clarifying subtle but important points (for instance, I really appreciate how she explains in detail that the term “First Triumvirate”, as applied to the agreement between Pompey, Crassus and Caesar, is absolutely incorrect, even though it still pops up occasionally in current accounts of the Roman Republic; p. 8).

My main objection has to do with the bibliography, which is limited, with very few exceptions, to books, chapters and articles written in English. Whether it be a decision of the series editor or the publishing house, I feel that this shortcoming does not faithfully reflect current trends in academia, for a large number of copies of this book will doubtless be bought by people and institutions, other than Anglophone universities, and read by them. A search in www.worldcat.org shows that the book is already in many libraries in the Netherlands, Germany, Italy, Spain, France and Mexico, although I am sure that a more comprehensive search would reveal that it is also now on the shelves of many other non-Anglophone libraries. Ancient history and Classics figure among the disciplines in the humanities that include scholars in a global conversation (or at least try to). I am confident that whoever picks up this book with a view to broadening their knowledge of the subject would benefit from references to German, Italian, French and Spanish scholarship in this respect, such as A.-C. Harder’s book on the relationship between brothers and sisters in the Roman Republic (regarding Clodius and his sister Clodia), Moreau’s book on the Bona Dea trial, Schubert’s, Dareggi’s and F. Rohr Vio’s studies on Fulvia and on other powerful women in the Late Republic, Ferriès and Delrieux’s perspective on the coinage that might depict Fulvia, and Borgies’ analysis of the propaganda struggle between Octavian and Antony, among other topics.[1] Neither does the decision not to include such references do good service to an otherwise magnificent series, nor does it reflect the current state of research on the topic.

To my mind, this is a well-written book, accessible for undergraduates and graduates (the paperback edition is very affordable), that offers a well-balanced, informed and nuanced picture of a powerful and important figure of the Late Republic. Schultz has crafted a very compelling narrative, leaving aside all clichés and analysing in depth the politics at the time. All in all, it is a worthwhile read.

Notes

[1] A.-C. Harders, Suavissima Soror. Untersuchungen zu den Bruder-Schwester-Beziehungen in der römischen Republik, München 2008. P. Moreau, Clodiana Religio. Un procès politique en 61 a.v. J.-C., Paris, 1982. C. Schubert, “Homo politicus – femina privata? Fulvia: eine Fallstudie zur späten römischen Republik”, in B. Feichtinger and G. Wöhrle (eds.) Gender Studies in den Altertumswissenschaften: Möglichkeiten und Grenzen, Trier, 2002, 65-79. G. Dareggi, “Sulle tracce di Fulvia, moglie del triumviro M. Antonio”, in G. Bonamente (ed.) Augusta Perusia: studi storici e archeologici sull’epoca del bellum Perusinum, Perugia, 2012, 107-115. F. Rohr Vio, “Dux femina: Fulvia in armi nella polemica politica di età triumvirale”, in T. Lucchelli and F. Rohr Vio (eds.) Viri militares: rappresentazione e propaganda tra Repubblica e Principato, Trieste, 2015, 61-89. M.-C. Ferriès, F. Delrieux, “Un tournant pour le monnayage provincial romain d’Asie Mineure: les effigies de matrones romaines, Fulvia, Octavia, Livia et Julia (43 a.C.-37 p.C.)”, in L. Cavalier, M.-C. Ferriès and F. Delrieux (eds.) Auguste et l’Asie Mineure, Bordeaux, 2017, 357-383. F. Rohr Vio, Le custodi del potere. Donne e politica alla fine della Repubblica romana, Roma, 2019 (now translated into English in an updated version: Powerful Matrons. New political actors in the Late Roman Republic, Zaragoza, 2022). L. Borgies, Le conflit propagandiste entre Octavien et Marc Antoine, Brussels, 2016.