Like the author of this book, I consider myself a Classical Archaeologist; I am, moreover, his approximate contemporary (b. Nov 1929) and our paths have crossed several times.

I admit, however, that I was unprepared for the extent of John Boardman’s bibliography (pp.214-54 of the book under review). It lists 402 articles (18 written jointly, the last dated 2018); 18 books edited (some jointly); 17 joint books (the last, on Alexander the Great, appearing in 2019); and an astounding 43 single-author books, some appearing in more than one edition, many of them also translated into various languages. Ten more items are listed as forthcoming. To be sure, this prodigious productivity includes some obituaries, a few prefaces written to others’ publications, and solicited contributions to volumes honoring distinguished scholars; but several single citations deceptively “hide” multiple entries in dictionaries, encyclopaedias, the Fasti Archeologici and, primarily, the Lexicon Iconographicum Mythologiae Classicae, for which Boardman was among the initial board members and frequent contributor. His involvement in other editorial boards, e.g., the Corpus Vasorum Antiquorum, and various additional enterprises, coupled with his extensive traveling for both pleasure and profit bespeak an almost incredible efficiency and energy. Among our students it was rumored that Boardman could write a paperback during the weekend…

In terms of organization, however, this autobiography betrays its piecemeal origin. “Note to Reader” (unnumbered page) mentions that it was started some ten years ago and was initially intended primarily for family. It then occurred to the author that the span of time it covered had indeed seen momentous changes in academia and the world at large that deserved mention, although not necessarily in logical order. The resulting text is in three Parts, each with multiple sub-headings: I: Family life, traveling, excavations, personalia; II: Academic life at Oxford and elsewhere; writing of books, pupils, travels; III: Ancient gems and their publications. Within each section, some comments are extensive, others are half a page and sketchy. The narrative is interrupted about halfway by 79 photographs, many of them in color (unnumbered, pp.127-68); three more, less personal, appear on pp. 215-16. An “Afterword” (p. 233) hints at regretted omissions, fading memory, uncertain health; it concludes: “In March 2020 I have given up driving.”[1]

I have therefore decided to summarize events only briefly, emphasizing rather aspects of John Boardman’s personal development that have struck me as especially relevant. I also refrain as much as possible from commenting on typically British aspects of life (the pleasure of eating kippers! p. 12), which require specific cultural and topographical knowledge, stressing instead references to places and people meaningful to an international (especially American) readership. But early life was important in shaping his future, and his remembrance of antebellum England seems the most vivid and detailed.

He was born in Ilford, Essex, close enough to London that he could see the Thames estuary and docks, and, in war time, witness the Battle of Britain and the Blitz. His family house, revisited years later, had a colorful garden—the first of several that will be described with pleasure and bespeak a real interest in vegetation. As a child he lived in an adult world: his only brother was almost 16 years his senior and his parents at his birth were old, by 1927 standards, but both came from quite large families and we learn much about relatives and influential “Aunties” who provided a warm and supportive background. World War II arrived soon enough to affect his childhood, and he repeatedly deplores (e.g., pp. 16, 22, 36) that he “was never a teenager”—something that surely happened also to many of his contemporaries, including this reviewer, regardless of location and type of war experience. We hear (p. 4) the sirens announcing the beginning of the hostilities, on a Sunday, as he is coming back home from a swim in a park, and once the V1 and V2 start flying, one explosion was close enough to knock him off his bicycle. Many of his neighbors were evacuated to safety but he remained at home and continued to attend school.

He seems almost deprecatingly modest about his academic progress; he was “caned” once by the headmaster of the Redbridge School (p. 13) for being too talkative, and paints himself as an average student although he keeps receiving awards, often financial. The next level of learning, at Chigwell (an old school once attended by William Penn) encouraged memorization (important in his future), exposed him to Latin (“intensely boring and mechanical”) and Greek (“magical”) and to a mentor (the Headmaster, Dr. R.I. James) who made him compete for a scholarship at his alma mater, Magdalene College, Cambridge—John won top prize and never regretted making that choice over Oxford.

That part of his life also included serious diseases—measles, scarlet fever, diphtheria—and the realization (p.23) that he was daltonic (red-green colorblind), which later prevented him from joining the RAF. But he also mentions his habit of sketching objects to remind himself of topics during lectures or of exhibits in museums, which he kept up throughout his life and even, in the 1990s, led to his taking formal classes in drawing.

At Cambridge, John was primarily influenced by two archaeologists who played a major role in his choice of academic field: Charles Seltman and Robert Cook. The former was “something of a dealer as well as scholar, but a great numismatist and inspiring lecturer” (p. 34) whose classes on Greek art made John decide to pursue that subject. More importantly, Seltman showed the students his own collections and made them handle electrotypes of Greek coins, which I find prophetic of John’s lifelong interest in carved gems and his ease with collectors and dealers. The second man, Cook, was an expert on Greek vases and “instilled a respect for objects and for accurate inspection and description” (p. 33) which, as John often deplores, are frequently replaced today by theory unaided by close observation. Cook urged his gifted student not to waste time for a doctorate but to go to Greece and get something published as soon as possible. Both this attention to minute details in something as small as a coin or a carved gem, and the urgency in publishing personal observations and unknown collections characterize John’s enormous production through the years, to an extent which I (personally more interested in larger objects) had not realized until I read Part III—the more detailed discussion of his research in the entire book. I also wonder whether his visual limitations were, subconsciously, to fuel his interest in two-dimensional (i.e., manageable) renderings.

John’s first Greek interlude occurred in his early twenties, 1948-50. He attended the British School in Athens, which still stands so close to the buildings of the American School that the two institutions share tennis courts.[2] They differ, however, in that the latter has a regular program of instruction and guided travels through the country, whereas the former leaves the members free to pursue their own research. Yet socially they join forces, and John felt himself “coming of age” as it were, in the company of many American students. Their names should be familiar to many archaeologists: Eve Harrison (who taught John how to dance), Evelyn Smithson, Anna Benjamin, and “the seniors”: Jack Caskey, Carl Blegen, Bert Hill, Oscar Broneer, Rodney Young and, of the Agora excavators and researchers, Lucy Talcott, Alison Frantz, Dorothy and Homer Thompson, Eugene Vanderpool.[3]

John pursued his own exploratory travels, alone or occasionally with friends, and comments repeatedly about modes of transportation, primitive conditions and glimpses of a Greece many would not recognize today (e.g., Delphi). Trips included visits to Sounion, Salamis, Crete, Delos and especially Boeotia, on assignment by Vincent Desborough who had asked for somebody to photograph vases in storage at the Chaironeia Museum.[4] John duly accomplished the task, the first of many he was to perform eventually to create his own records; but he often stresses how lucky he was throughout his career to work with presses (e.g., Thames & Hudson) or collections (e.g., the Beazley Archive) that placed their vast photographic holdings at his disposal. Those of us who have struggled to collect illustrations for our publications realize what an advantage such access represented.

One more lucky result of this Greek stay was John’s first research project. Cook, his Magdalene mentor, had suggested that he study Melian Archaic pottery, but that material was still inaccessible in post-war Greece. Semni Karouzou, the moving force at the newly reopened Athens National Museum, proposed instead that he work on Eretrian (Euboean) vases and, although this seemed aesthetically indifferent material, it later proved to be highly significant about Greek expansion in the ancient world and provided one more dominant interest in John’s career.

In Greece John first met Sheila Stanford, whom he married in England, in 1952, shortly after an early discharge from his (deferred) Army service.[5] She too had supportive relatives and, as mother of two children (Julia and Mark) turned John into a family man. She was “an artist, not an academic” who took responsibility in “prospecting” and finding suitable, progressively larger, accommodations in various locations, each with lovely vegetation, until their present one, at Woodstock, not far from Oxford where John now goes every day for lunch and company. Sheila, who had accompanied her husband on many of his travels, died in 2005. Her place was then frequently taken by Julia (occasionally with her companion, Jeremy, an ex-Guards officer and former Equerry to the Queen Mother—see photographs) who is now a major helper to her father. John had his own share of illnesses which he, at 90, summarizes from childhood to old age (pp. 117-21). I only need mention his (perhaps?) sensitive stomach, because of his surprising emphasis on good food and accommodations throughout all his travels.[6]

Excavational experiences, although significant in their own way, do not represent a major component of John’s career but reflect an important facet of his archaeological mentality. The first (two campaigns in 1949 and 1950) took place in Turkey, at “Old Smyrna” (modern Bayraklı), together with Sinclair Hood, who proved to be a great field mentor “in terms of observation and thorough reporting,” which resonated with John’s personal inclinations. More telling is the subsequent comment (p. 46): “We were not too hampered in those days by scientific aids and had to be totally self-sufficient in recording and analysing what we found, and in trying to make historical sense of it on the spot, if possible, not ten years later, if ever.”[7] During a second Greek stay (as Assistant Director of the British School, 1952-55) John worked on the Black Figure Attic vases found in that previous excavation, learning to recognize and attribute hands and groups and also beginning to be interested in ancient gems, but “basically I was still a pot person” (pp. 55-56). At Knossos (Crete) he then helped organize and publish some Protogeometric and Orientalizing material excavated there many years previously, having learned “the merit of never leaving things undone which could be done immediately” (p. 57). Then, under a new Director, the congenial Sinclair Hood, John was assigned his own dig, on Chios. It is obvious that the island occupies a special place in his memory, since several pages are devoted to its description and John returned to it for conferences and congresses. The site itself, Emporio, on a steep hill, yielded an important early Archaic Ionic temple, but also Classical and late Roman material. More varied finds (from prehistoric to after the arrival of the Arabs) were unearthed on the shore itself and even underwater. John’s comment (p. 61) is a sort of testament to his career: “I am thankful that I never followed the general practice of today, handing over special material to some ‘expert’ rather than trying to become expert myself. I have little patience with archaeologists or indeed any antiquarian who never looks outside ‘his subject area.'”[8]

He states his impatience also in teaching undergraduates (p. 189) but enjoyed one-on-one (i.e., PhD) contact if the “other one” was rewarding. He also loved giving public lectures (especially on the Parthenon), and thus participated in many national and international conferences and lectureships abroad. At Oxford he had numerous students, of various nationalities and three of them rate extended mentions because of continuing personal involvement: Claudia Wagner, Gocha Tsetskhladze, and Olga Palagia. The first, a German with an Oxford PhD, became involved with the Beazley Archive and the collection of gem casts, turning into an expert in the study of gems and therefore of great help to John himself. The second was born in the Republic of Georgia; his main interest is the Black Sea area, where he organized several Pontic conferences and international symposia. He edited a Festschrift in John’s honor (2000); a previous one (1997) involved John’s many Greek students and was edited by Olga Palagia, a sculpture specialist and Professor at Athens University, who with her husband remains a steady contact.[9]

Additional honors elicit perhaps the briefest accounts. The conferring of the Knighthood rates only eight lines (under the Oxford subtitle, p. 188), no actual description of the event itself but a photograph showing John in the attire he had to rent for the occasion. The Onassis Prize ($120,000) given at the French Academy in Paris, gets noted for allowing guests to dinner (p. 211). Election to the British Academy (Archaeology Section) and the Royal Academy (Ancient History) are discussed at greater length, but again almost in terms of meetings and, as usual, meals.[10]

How John managed any teaching is amazing, given his travel accounts. Numerous and fascinating, whether undertaken for research or for pleasure (e.g., the Swan Hellenic Cruises), they cover most of Asia, part of the Near East and Africa, a great deal of Australia as well as Europe, and even the New World (Mexico), many of them revealing his ever expanding interest in the Greeks overseas and their (even if remote) influence on others’ arts and cultures, some as remote as India and China. Of particular interest to Americans are his trips within the United States, especially his first encounter with New York in 1965, when he took over Prof. Evelyn Harrison’s classes (and apartment) for one semester while she was on sabbatical leave from Columbia University. He found the graduate students “bright beyond expectation, and a good match for Oxford but with perhaps a more vital and original approach to their work” (p. 76). He also met all the luminaries of the time (including the legendary Margarete Bieber), helped Edith Porada measure the Morgan Library eastern seals for publication, and visited many museums, but it was the city itself and its vitality that took him by storm, and he “did all the right things,” including using the Staten Island ferry and experiencing the Empire State Building. In 2006, when he revisited, he found New York seemingly unchanged in all important aspects, as contrasted with London.

Subsequent trips to the United States are recounted without strict adherence to chronology and even to proper nomenclature. For instance, John mentions giving the Mellon Lectures in 1994, but I attended the first of them, in Washington D.C., on March 28, 1993, and it was held at the National Gallery (not the National Museum), under the auspices of CASVA, the Center for Advanced Study in the Visual Arts, whose scholarly Dean (not Professor) at the time was Henry Millon, who had moved back to the States after being the Director of the American Academy (not School) in Rome, 1974-77.[11]

During such trips John managed to visit also auction houses, dealers in ancient art, and wealthy collectors, especially Leon Levy and his wife Shelby White, who had made major financial contributions to both the Beazley Archive and the Metropolitan Museum, as well as other institutions of higher learning. But these generous philanthropists also acquired objects demonstrably smuggled illegally out of their countries of origin.

John’s great interest in ancient gems, so clearly detailed in Part III of his autobiography, is seen as an extension of his study of hands and workshops in vase painting, which made him a towering successor to the great Beazley. But he makes no distinction between well established, antiquarian holdings and more modern ones still growing. To be sure, ancient gems, like coins, usually traveled and seldom were found where they were made. Numismatists have therefore claimed to be exempted from the strictures established by the Geneva Convention for the preservation of antiquities. But gems, like coins, can be forged, and any illicit acquisition can raise doubts about their authenticity. In recent years, several museums have had to return (important) objects to their country of origin, when that could be established. Other items are still among museum holdings but under a cloud of suspicion.[12]

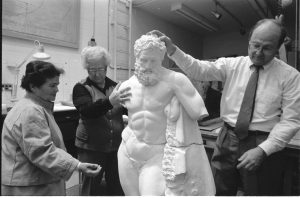

In his approach to dealers and collectors John Boardman is clearly still a man of the 20th century, but his investigation of gems and finger rings in 18th- and 19th-century (or earlier) collections, as well as more recent ones (ca. 18) have not only required deep archival research into distinguished owners and locations, but have also enabled him to develop modern techniques of casting and photographing intaglios, with the repeatedly acknowledged help of photographer Bob Wilkins and of other scholars. Novel technology has allowed improvement not only in analysis but also in publishing. The series of books already in print and others announced as forthcoming represent a phenomenal achievement that therefore should not be overshadowed by ethical (21st century) criticism. The final words in the title of this autobiography read The Story so Far and may hint at a welcome second (revised) edition or a continuation of contributions by this most prolific of authors.

A final reflection makes me review my own involvement in archaeology as compared to John Boardman’s. In some respects, we have followed a similar trajectory: I too greatly profited from my early stay at the American School in Athens (1955-57), had (limited) excavational experience (at Phaistos, Crete, 1956)—which convinced me that I was no field archaeologist—have had some editorial experience (American Journal of Archaeology, 1977-1985), was at CASVA (1986), held the Geddes-Harrower chair at Aberdeen, (1989), did the grand lecture tour in Australia (1992), and traveled abroad extensively. Like John (cf. his pp. 174-75), I enjoy tackling scholarly puzzles and pay great attention to close analysis of my subjects, although I concentrate on sculpture rather than vase painting. In two respects, however, we differ fundamentally: teaching and research direction. I always loved having all levels of students who stimulated my own thinking and forced me to revise “orthodox” positions in archaeology. And whereas John looks for what is Greek or Greek influence in all areas of the ancient world, I try to discern what is not Greek in classical art, separating the later accretions and varying intents behind monuments that appear to copy Greek prototypes—the famous Roman copies that I began to challenge in my early writings and which are now being re-evaluated by new generations of scholars at all levels.[13] Perhaps future years will reveal which position best survived the scrutiny of evidence—the answer probably lies somewhere in between.

Notes

[1] An Index of People and one of Places (255-61) must have been compiled by helpers or by the publishing Press. They are both incomplete (with the first list often including only the surname, omitting titles, initials, etc.) and, occasionally, erroneous, but they are helpful nonetheless. In the Bibliography, one book is cited twice under different subheadings. Stricter editing could have avoided repetition of sentences, occasionally even two within the same paragraph (p. 204)

[2] This proximity, among other benefits, inspired John to learn to play tennis. In his earlier studies he had tried to avoid heavy sports (one hit to the head may have caused some later health problems), but at Cambridge he had joined the rowing club and had done well enough to be proud of his participation.

[3] Of the British members, I confess I only recognize archaeologist Brian Shefton, who recurs elsewhere in this autobiography and whom I met personally in later years. John also mentions making many Greek friends and intentionally avoiding stressing the academic part of his stay in Greece.

[4] As part of this trip, John mentions visiting a Mycenaean tholos tomb and its annex with its unusual carved ceiling (p. 40) but although the finds from it were stored in the Chaironeia museum, the structure itself is at nearby Orchomenos.

[5] “It was unquestionably the best thing I have ever done” he writes (p. 54); on p. 116 he also states: “No other person, even main family, has meant so much to me.” Of their two children, Julia is frequently mentioned; Mark (twice married and with a blended family of four children) is a major helper in John’s advanced age (p. 123).

[6] One bout of illness deserves mention because of its unusual circumstances. It was so protracted and dangerous that he endured from Pakistan to China but finally had to be taken to a Uighur hospital with primitive facilities but helpful antibiotics that restored his health…and his lost weight (pp. 94-95).

[7] A dislike for theory unaccompanied by objective (or with flawed) evidence, recurs in one specific case (p. 199) and about tendencies at Cambridge in general (p. 188): “I have no heart for theory per se and mourn the loss of basic archaeological skills…almost totally abandoned by some classical archaeologists and even art historians,” for which anthropologists, with the different nature of their evidence, are partly to blame and have created a divide of interests between the two major universities.

[8] In 1963 at Tocra (Libya, ancient Taucheira), the finding of a cache of vases on the beach attracted John to do one more research and study in collaboration with John Hayes, a vase expert. It resulted in two volumes, after which he decided he “had had enough excavation” and never again (p. 75).

[9] A third volume, in honor of John’s 90th birthday. Greek Art in Motion, has appeared in 2019; see also pp. 124-25. For other students’ mentions, see pp. 198-202; also p. 222 for Claudia and gem studies.

[10] The British Academy had conferred on John the Kenyon medal but he missed its award because of poor health, receiving it later in a more informal occasional (p. 188). This seeming indifference for recognition is even expressed in the fact that the automobiles he owned were never a status symbol and usually fell to pieces before they were replaced (p. 122).

[11] The correct date is given on p. 176; CASVA sponsored the Mellon lectures by the annual Kress professor. For my comments on the lecture and the resulting book, see BMCR 1995.04.04. John must have remembered seeing me on that occasion, but his suggestion that I “nabbed” him to speak to my students for Pennsylvania (my emphasis, p.79, repeated as “hijacked” on p. 176) is an impossibility; not only was I already retired from Bryn Mawr (officially starting in Jan. 1994) but if “Pennsylvania” meant UPenn, I could not possibly have arranged for him to speak at another university. I can moreover find no trace in my departmental records of Prof. Boardman’s lecturing at Bryn Mawr College at the time. Yet he twice comments on the difficulty of having to rearrange his slides for the occasion.

Other possible misrecollections: in Washington the Sackler Museum is mentioned but it is the A.M. Sackler Gallery of the Smithsonian, next to the Freer Gallery, which was probably also of importance for the research mentioned. In “Rochester” (p. 80) John lectured for one of the Societies of the Archaeological Institute of America (the AIA), not the American Archaeological Association. Under “Stanford, San Francisco” (p. 64) a mention of going across to Yale University is a geographic impossibility. In “Baltimore” (p. 85) the Museum cited is probably the Walters Art Gallery; and under “Boston” (same page), the museum of model flowers (“very odd”) must be the Harvard University Museum of Natural History housing the famous Ware Collection of Blaschka glass models. Given the amount of traveling and the span of time involved, these imperfect recollections are nonetheless remarkable, but I cannot resist: on a visit to the Louvre (p 104) he cites the Parthenon fragments and, on the stairs…the Venus de Milo; he obviously meant the dramatic Nike of Samothrace.

[12] On dealers and Christie’s Auction House see, e.g., pp. 83, 198; on the Swiss collector George Ortiz: pp. 177-78; on Shelby White and Leon Levy: pp. 79, 81, and passim. The Levy White acquisition of the upper part of a Herakles marble statue has been demonstrated (on Sept. 25,1992) at the BMFA, through casts and perfect join, to belong with a lower torso from Turkey. The Herakles (recomposed) is now “on loan” between the Boston Museum and Antalya. For possible (unresolved) forgeries, see, e.g., the Warren Chalice in the British Museum or the Getty Kouros in Malibu. I do not support the extreme position of a lawyer (p. 178) who thought that unprovenanced antiquities should be destroyed, but certainly financial considerations and losses in having to return items to countries of origin are convincing museums to be cautious in their purchases. In my correspondence with Dietrich von Bothmer about the notorious Euphronios Krater bought by the Metropolitan and returned to Italy, he argued that nowadays even illegitimate children were accepted by society. I wrote back: “Nonetheless, we still prosecute for rape.”

[13] On pp. 178-81 John alludes to his writings about “The World of Ancient Art” including eastern Eurasia, China, Egyptian, pre-Columbian and Roman art— the last in a book now with Archaeopress for publication. It will be interesting to see his reactions to some of the new positions in that field.