This is an ambitious book. It aims to show that Aristotle has a coherent account of artefacts, thereby challenging the widespread assumption that Aristotle uses artefacts primarily as examples or analogical cases.[1] According to the account ascribed to Aristotle, artefacts are not merely chunks of matter or accidental beings, but hylomorphic compounds that possess substantial forms. As far as I know, this proposal has not been explored in such detail in Aristotle scholarship before, making it a novel contribution to existing discussions. Furthermore, the book aims to contribute to contemporary metaphysics, where the ontological status of artefacts has received increasing attention, especially among Neo-Aristotelians interested in hylomorphism.

The first two chapters of the book discuss the Platonic heritage: Plato’s ontology of artefacts and Aristotle’s use of artefacts as counterexamples or central elements in counterarguments against the Platonic theory of Forms. The author proposes that Aristotle’s account of artefacts can be considered an outcome of this Platonic heritage, though this proposal is not developed in great detail. I would like to focus on what I find to be the most exciting part of the book: Aristotle’s ontology of artefacts. The author begins to develop this in the second half of Chapter 3, with the remaining chapters elaborating on what I would identify as the book’s main thesis: that artefacts are genuine hylomorphic compounds, without being substances. Readers most interested in the implications for contemporary metaphysics should focus primarily on the conclusion of the book (as well as the later sections of Chapter 3).

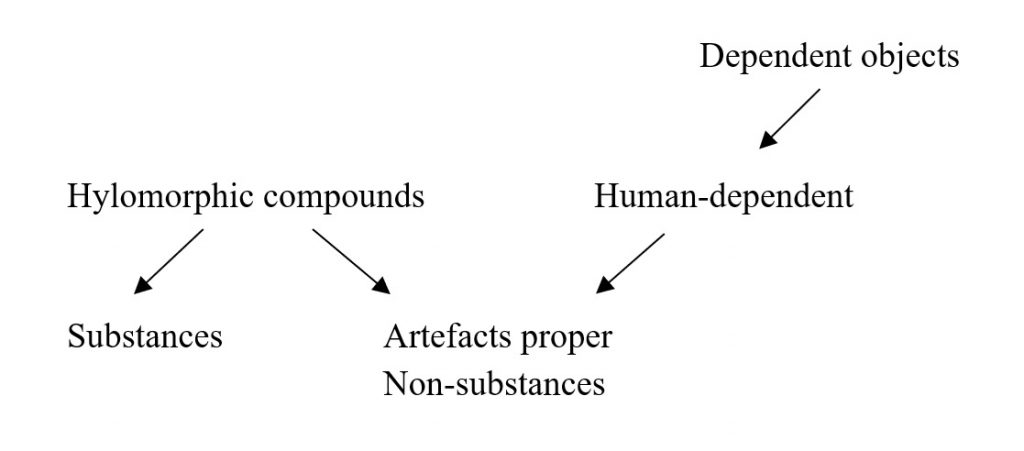

The ontology of artefacts developed in Chapter 3 relies on Aristotle’s characterization of natural beings as those that have an internal principle of change and rest, which is taken to be the main distinguishing feature between natural beings and artefacts. The resulting ontological classification can be presented as follows (note that this schema is my own; the author may present it differently):[2]

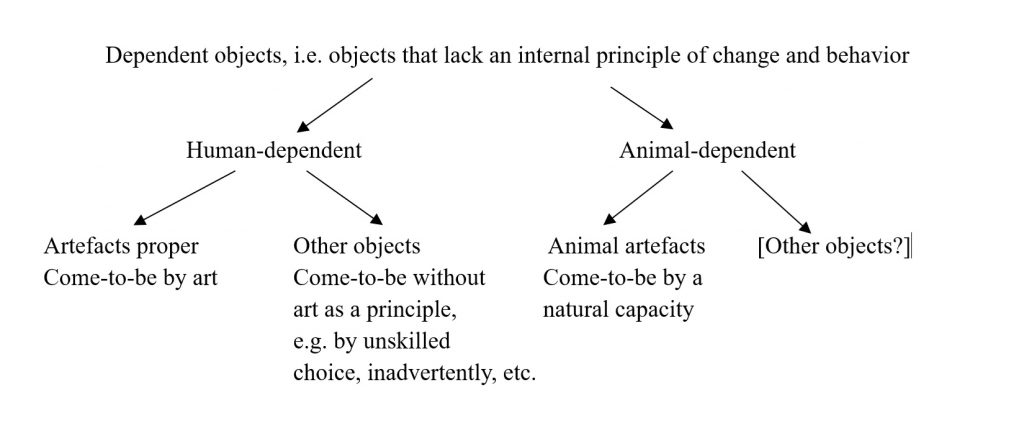

The author ascribes to Aristotle a distinction between artefacts and artificially caused beings, as well as between natural beings and naturally caused beings. Although typical artefacts come-to-be by art, there can be natural beings which are artificially caused. The example given is domesticated plants like domestic olives, which nonetheless remain natural beings with an inner principle governing their behavior. Indeed, the author argues that mixtures, as homoiomerous bodies, are natural beings, even though some of them (e.g., theriac, a drug made of dozens of ingredients) come to be only through art. There are also cases of naturally caused artefacts: animal artefacts (e.g., a spider’s web or a bird’s nest) are not artificially caused, given that non-human animals do not possess art. They are rather naturally caused in a secondary sense, by an innate capacity. But insofar as animal artefacts lack an inner principle governing their behavior, they fall under dependent objects and can be compared to human artefacts.

Chapters 4-7 focus on defending and developing the view that artefacts are hylomorphic compounds without being substances. It is not immediately clear how this view of the ontological structure of artefacts relates to the ontology developed in Chapter 3. Presumably, while the latter chapter focuses on what distinguishes typical artefacts from natural beings, the following chapters focus on what they have in common: even though artefacts lack an inner principle of change, they too are hylomorphic compounds. This similarity brings along the need to identify further differences between artefacts and natural hylomorphic compounds, including differences that explain why the latter are substances, while the former are not. Thus understood, we may expand on the schema presented above as follows:

Chapter 4 discusses three considerations in support of the view that artefacts are hylomorphic compounds. The main consideration is that, in Physics 1.7, Aristotle ascribes to artefacts a genuine, unqualified coming to be, which entails that artefacts have both matter and substantial forms. This consideration distinguishes artefacts from heaps and accidental compounds like Socrates-being-white, but it would also exclude cases such as using a rock as a paperweight, as this does not result in the existence of a new object through unqualified coming to be. The author argues that the form in the artefact that drives the relevant change in the matter is the one in the mind of the artisan, which is identified with art. Indeed, there is “only one form but… it has two modes of being: the form in the object and this same form as it is thought in the mind of the artisan” (p. 142).

Chapter 5 identifies the form in the mind of the artisan, which is external to the object, as the only form with efficient powers. The author rejects the theory that the form in the mind of the artisan is transmitted to the object, arguing instead that the form in the artefact lacks efficient causal role and is thus inert. This is compatible with taking the distinguishing feature of artefacts to be the lack of an inner principle of their behavior. What role, then, does the form in the artefact play for Aristotle? This question is taken up in Chapters 6 and 7, from the perspectives of a natural philosopher and a metaphysician, respectively.

From the perspective of a natural philosopher, forms of artefacts are specifiable as functions. By examining the relationship between the form (as function) and its matter (both diachronic and synchronic), the author concludes that the form—though it inheres in the object—is external to its matter, and their relation is accidental. From the perspective of a metaphysician, as addressed in Chapter 7, forms (whether natural or artificial) are primarily structuring principles, in virtue of which the material parts form a unified whole. The author argues that although the parts of artefacts are unified by their form, artefacts are unified wholes to a lesser degree than natural substances, which explains why artefacts are not substances. The author relies on Metaphysics Z.13 to provide a criterion of substantiality, according to which no substance can be composed of substances existing in actuality. Since the artificial parts are not potential but actual, the identity of parts is not “swallowed up by the whole itself” (p. 328) and so the whole lacks the relevant unity required for substantiality. The author thus ascribes to Aristotle what she calls a scalar view of unity and a binary view of substances: since “artefacts are less of a unity (scalar view), they are not substances at all (binary view)” (p. 239). The final chapter of the book revisits the material discussed in previous chapters, adding the perspective of a user of an artefact.

This is a rich and well-researched book that will influence future discussions on Aristotle’s account of artefacts. However, as mentioned earlier, it is an ambitious work: it aims not only to present Aristotle’s views on artefacts but also to explore their Platonic background and contribute to contemporary metaphysical debates. While the author offers a complex and sophisticated account of Aristotle’s hylomorphism concerning artefacts, based on his physics, I find some of the underlying metaphysical notions and issues (e.g., separation, two modes of being) to be underexplained or underdeveloped.

Most notably, the issue concerning the criterion of substantiality and artifacts would benefit from further discussion. The author attributes to Aristotle a binary view of substantiality. But what is at stake when choosing between a binary and a scalar view of substantiality? Without a clear understanding of the substantive differences between these views—if there are any—it is difficult to evaluate the textual evidence in support of a view under discussion. Furthermore, the author focuses on the criterion of substantiality in Metaphysics Z.13. Is this supposed to be the criterion of substantiality for Aristotle, or are there other criteria as well? In particular, why does the author overlook or ignore ontological priority (or independence or fundamentality) as a criterion of substantiality, especially given the recent attention this notion has received in both Aristotle scholarship and contemporary metaphysics? The latter question arises also in connection with the author’s classification of artefacts as “dependent beings”. Is the dependence involved (also) ontological? If so, how should we construe it? Indeed, how does the author understand Aristotle’s ontological project in this context? Does she view Aristotle as merely classifying different kinds of beings, or as (also) ranking them hierarchically? Or does she consider the project to be mainly definitional, distinguishing artifacts from other kinds of beings? I am confident that readers will have other questions after working through this thought-provoking book.

Notes

[1] The only other book-length treatment of Aristotle’s metaphysical views on artefacts (E. G. Katayama, Aristotle on Artifacts: A Metaphysical Puzzle. Albany: SUNY, 1999) was published more than two decades ago.

[2] Regarding the category “[Other objects?]” under “Animal-dependent”: there is at least one claim suggesting that the class of animal-dependent objects is seen as “including artefacts proper and other objects lacking an inner principle” (p. 99), but, as far as I can tell, there is no further discussion or examples of such objects.