[Authors and titles are listed at the end of the review]

Contributions to the volume under review were presented as lectures at the University of Cologne in December of 2019. A brief editorial foreword offers a justification for the book’s title and contents: it arose out of a decade-long project under the same name at the University of Cologne and celebrates both the 20th anniversary of the announcement of the Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae (CIIP), along with the 80th birthday of one of its central architects, Werner Eck.

Hannah Cotton’s introductory contribution presents a prehistory of the CIIP and the study of “Classics” in Israel, where “concepts native to Germany of the nineteenth century” arrived in Palestine on the minds of now famous scholars: Moshe (Max) Schwabe, Avigdor (Victor) Tcherikover, and Yohanan (Hans) Lewy. (1) Cotton’s analysis is studiously archival, following documents attesting the importation of Altertumswissenschaft to Palestine by settlers and their early attempts to collect epigraphic material about the region. The essay has an historiographical frame but an apologetic aim: twice Cotton refutes the idea that including semitic language inscriptions next to those in Latin and Greek is an exercise in “political correctness” (2, 7) and the essay introduces a refrain common among the volume’s contributions: “the richness of the epigraphic tradition can come fully into its own only when epigraphic texts in different languages…are studied together.” (7)

Benjamin Isaac’s chapter presents a survey of inscriptions from Palestinian towns with the aim of elucidating four broad categories of inquiry related to who was active in each area, and in what capacity. Throughout Isaac points to the value of epigraphic material to amend impressions left by literary and archaeological data. While systematic in broad strokes, the treatment of regions is haphazard, giving the impression that it is compiled from notes with little editorial intervention. One example is a section on literary sources for Eleutheropolis containing a paragraph which reads in its entirety, “The town had a good water supply.” (35) Treatment is inconsistent: a half-page of analysis on literary sources for Dor contrasts strikingly with four full pages of material on Ascalon (some of which is beside the point, though often charming, like a short etymological discussion of the English word “scallion”). Other inconsistencies render the chapter difficult to digest as more than a collation of data with general methodological observations tacked on either end, though even the method varies; at once fourth century mosaics are evidence for “early Christianity” (33) while material from 321 CE underscores that “Christianity did not arrive in Ascalon at a particularly early stage.” (22)

Avner Ecker’s short contribution shares many themes with Isaac’s. Both stress the value of epigraphic evidence en masse and the interpretive advances possible through attention to everyday objects which survive by happenstance, like “a clay seal 1.6 cm in diameter, stamped with letters no larger than 0.25 cm [which] lends a major contribution to the understanding of the variety of local administration in the Roman Near East.” (47) Isaac’s evidence largely answers questions regarding who, while Ecker’s “small inscriptions” on ostraca and bullae mostly address questions of what and when — in one instance overturning the common notion that Dressel 30 amphorae were used exclusively for trading wine, and in another suggesting that the administrative language of Maresha changed wholesale from Aramaic to Greek in the very first year of Seleucid rule. The latter, in particular, is an important interpretive advance, though as Ecker notes it is the starting point of his own ongoing study, and the insight was previously published by Ecker and others. Together, Ecker and Isaac’s contributions present a useful series of vignettes into the promise of epigraphic material and an apology for historians to use magnificent resources like the CIIP.

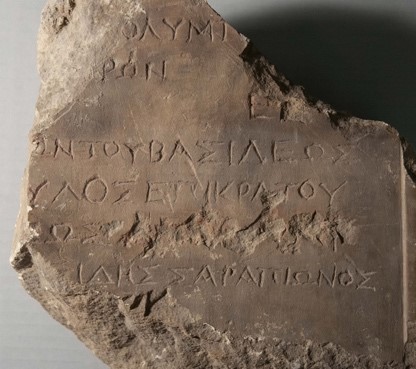

Johannes Heinrichs’ contribution is rather different. In it, Heinrichs considers three Seleucid-era inscriptions from Palestine in which kings names were erased, suggesting that the erasures are “clearly political.” (56) Heinrichs has, without a doubt, a strong historical imagination. I offer one example: his proposed reconstruction of events surrounding the incomplete erasure of a king’s name in Penn Museum 29-107-961, from Scythopolis.

“Letters rudely destroyed next to others partly preserved hint at violence on impulse. Since the list is a public document that underlines the city’s loyalty towards the Seleukid dynasty, it would not have been wise to wipe out the king’s name in a way that excluded retaining it as a whole in the public after repair. We may assume that local residents would have erased the name much more cautiously, just to avoid Seleukid suspicion concerning the city’s loyalty. Therefore, damage as grave as this, done to a politically significant document, must be ascribed rather to non-residents who just let out their rage against a Seleukid king in a riot. These men must have been strong enough to resist local opposition. Evidently it had not appeared wise to stop the act of destruction that probably affected more than one list on the stone. For some while — longer if more than only a single list was damaged — the riot must have caused considerable noise in a central and presumably crowded public place. The perpetrators could have been hindered in such a place if they were few and unarmed. But just that had evidently not happened. So the most probable causes are soldiers or mercenaries in a situation of tension, as time and again in history.” (58–9)

I include here an image of the inscription in question. Visible in the erasure is what appears to be one line of a delta to the left, the descender of an upsilon at the right margin, and perhaps remains of an iota as well. These data are the trusses supporting the narrative quoted above. Heinrichs’s imaginative proposal is not obviously wrong. It is, however, a far cry from “the most probable cause.” (59) Given that we know nothing about the use or display of this inscription, one might propose an alternative tale that is at least equally plausible: the inscription was displayed indoors, and at the dead of night a single objector with a small chisel ‘tink tink tink-ed’ at the letters until the king’s name was unreadable, slipping away unnoticed. Sometime later it was spoliated and finally deposited in a Byzantine-era reservoir, where it was discovered in 1925. Heinrichs’ two other inscriptions continue in a similar vein. In the end, the chapter is more historical fiction than analysis — useful as an exercise, but not as a published reconstruction.

Zissu and Gass present a significant departure from the preceding: a rather dry archaeological survey of a site in the Judaean foothills. As is often the case in survey archaeology, sparse pottery and absence of in situ architecture render significant interpretive advances difficult without test trenches, but the authors intriguingly propose to have identified a small scatter belonging to a Byzantine church marking the tomb of the biblical prophet Micah. The bulk of the discussion is dedicated to the “Tomb of Abraham,” a reused stone quarry boasting a number of dipinti.

Jonathan J. Price begins his chapter with a guiding principle from Eck: “no inscription, no matter how ethnically or culturally specific, can be properly understood when ripped from its immediate context.” (103) The insight underlies Price’s own, amply demonstrated throughout the CIIP and by numerous scholars, that in antiquity “Jews didn’t have their own private epigraphic language.” (104) Price reiterates that there is, at best, consistency within languages and small geographic regions which are rendered visible through comparison, as in Price’s clever argument about Levantine synagogue inscriptions in Greek picking up Aramaic formulae while Western synagogues do not. But there is nothing like a “Jewish epigraphic habit” to be found in the CIIP, nor should we expect one — even when ancient Jews moved, they brought with them epigraphic customs from their place of origin which remained distinctive, perhaps even over generations. Price’s chapter is laudable for its reminder to more confident interpreters of epigraphic material that we see our evidence only dimly; despite our wish for fuller pictures, epigraphers deal in fragments about which there is an outer limit of reasonable speculation.

Dirk Koßmann’s contribution extends a perennial interest of Eck’s — Roman imperial governors of Iudaea/Palaestina — into Late Antiquity, asking after continuities and changes in the structure of centralized governance and modes of monumental display. Koßmann’s chapter is the collection’s most detailed, addressing issues of definition, periodization, and bias in preservation: a granularity of analysis that renders the study more like a traditional research publication than the lectures printed on either side. It has a systematic and workman like quality, describing in narrative form the contextual details and interrelations between entries in an appended catalogue comprising over 100 inscriptions. In the end, Koßmann finds that the clearest difference between periods lies in the absence of honorific statuary for late antique governors and the predominance of building inscriptions naming an authorizing governor, instead. The state of the evidence suggests that mid-fifth century legislation like CI 1.24.2, prohibiting the use of public funds for such honorific statues, was perhaps heeded, at least in the east.

Among all of the contributions, Ameling’s concluding essay has the most distinct character of lecture notes, including a framing German “Also” before a bulleted list of introductory points. (183) With a case study in the monks of late ancient Judaea, the chapter explains the “Centre and Periphery” frame chosen for monastic inscriptions in CIIP volume IV, demonstrating that: “‘center and periphery’ are not absolute categories which can always be unambiguously assigned, but rather that they are dependent on the viewer’s position, and also that these concepts are scalable.” (185) Analysis focuses on spatial, spiritual, and societal centers and peripheries for Judaean monks, and Ameling’s title previews his view of monks as go-betweens. “In the end, the monk is defined as someone living between Jerusalem and the desert” (194) — nomads at the ready but definitionally waiting in the spatial and social wings in a “doubled marginality.” (195)

With one exception, essays in the collection retain their lecture form. Sometimes this is noted explicitly, as by Ecker, and sometimes it is simply clear from the bullet points, sentence fragments, and typos. Transparency about the format is commendable, but it requires one to ask the follow up question: why? What purpose does retaining the abbreviated format of a lecture serve the book’s reader when more framing, further analysis, and deeper engagement with relevant scholarship would make for a tedious and over-long lecture, but an eminently more useful publication? It is possible that the choice was expedient, allowing for a book to be produced quickly, with limited intervention on the part of the contributors. In this case, however, contextualizing labor is simply reassigned from contributor to reader. €69 is perhaps a small price to pay to have attended what was doubtlessly a wonderful, collegial, and informative gathering in Cologne, but is a book the best way to achieve that goal? In my estimation, the bar must be higher to justify production, and if production is undertaken, so too should the work to transform lectures into substantial and original research outputs.

All of the contributions would have benefitted from more conscientious copy editing. Typos and inconsistencies are rife: few which impede understanding the author’s meaning, but hundreds which needlessly distract the eye. A final round of quality control would have made for an easier read, too. In one instance, figures were apparently removed from Zissu and Gass’s survey but the text was not updated, rendering a mismatch between in text citations and plate numbers. The quality of the English in some chapters is occasionally difficult to understand: proficient, but hardly idiomatic. In a multilingual volume, one wonders why some authors decided to publish in their native German and others chose a different path. In the end, the book is a difficult read. For those willing to undertake the task, however, Centre and Periphery offers the benefit of attending a wonderful conference in Germany populated by brilliant, imaginative colleagues and in honor of one of the field’s great luminaries.

Authors and Titles

Walter Ameling, Vorwort

Hannah Cotton, The Pre-History of the Corpus Inscriptionum Iudaeae/Palaestinae

Benjamin Isaac, Cities of Judaea/Palaestina: Before and After the CIIP

Avner Ecker, Small Inscriptions and Big History: Dipinti, Bullae and Ostraca in the CIIP

Johannes Heinrichs, Erased Kings’ names in Late Seleucid Inscriptions

Boaz Zissu and Erasmus Gass, An Archaeological Survey at Horbat Basal (Khirbet Umm el-Basal), Judean Foothills

Jonathan J. Price, Insights into the Jewish Epigraphical Idioms from the CIIP

Dirk Koßmann, Die Vertreter der Reichszentrale in den Inschriften Palaestinas: Ein Vergleich von kaiserzeit und spätantike

Walter Ameling, Mönche zwischen Stadt und Wüste: Zentren und Peripherien