The use of aerial photography as an archaeological tool is exactly 100 years old. In December 1925 Squadron Leader Gilbert Insoll of the Royal Air Force photographed the crop marks which identified the location of the Neolithic monument later known as Woodhenge on Salisbury Plain in England[1]. The year before the archaeologist O. G. S. Crawford, recognizing the importance of understanding ancient landscapes from the air, flew over large parts of Wessex with Alexander Keiller[2]. A selection of the photographs they took were to be published in a book by them both four years later[3]. Then in the July of 1928, during an exceptionally dry summer, the RAF flew over the Roman town of Caistor St Edmund near Norwich, and a stunning photograph of the grid-plan of Roman streets and the outline of many of its buildings, visible from the air as crop marks in the ripening corn, caused such excitement that funds were raised and partial excavation of the site took place in the ensuing years[4]. Soon others were in the air making dramatic new archaeological discoveries, such as Father Poidebard’s survey of Roman frontier systems in Syria and Jordan, published in 1934[5], and Jean Baradez a decade later recording hitherto unknown Roman forts and irrigation systems in Algeria[6]. From those pioneering days archaeological survey from the air has gone from strength to strength and become an indispensable part of the discipline.

Broadly speaking, one can divide books on aerial archaeology into two separate groups. One is those that deal with new discoveries, sites revealed by cropmarks, soil marks, shadow marks and sometimes even snow marks. Photographs taken from the air recording such features have made dramatic advances in knowledge, but for climatic and environmental reasons such research has been largely confined to countries in northwest Europe, especially Britain, France, Germany and to a much lesser extent parts of Italy[7]. The second type of book, generally aimed at a more “popular” audience, is that which presents photographs, usually in colour, of already known archaeological sites which happen to have been taken from the air. Raymond Schoder’s Ancient Greece from the Air fifty years ago was a pioneer of this genre, at a time when gradually decreasing publishing costs made colour reproduction possible, the use of which made such works immensely more attractive[8]. Many others have since followed in its wake. I think in particular of the striking volumes of Georg Gerster, also covering above all Greece, but Syria, Iran and elsewhere[9] as well, and other books recording sites from the air in Italy, Germany, Jordan, Turkey, Albania and Britain[10]. As Schoder wrote in 1974, “an archaeological site seen from the air … is understood as a unit, not piecemeal in sequence as is necessary on the ground [and] the interrelationship of its buildings in size, position and arrangement becomes more clear”[11]. Therein lies the attraction of the genre. The book under review falls firmly into this second group.

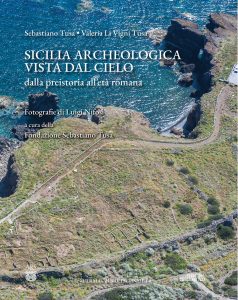

The principal purpose of Sicilia archeologica vista dal cielo is to publish 49 fine photographs of Sicilian archaeological sites taken from the air by well-known Sicilian photographer Luigi Nifosì (the total is 50 if one includes the cover’s photograph, not reproduced elsewhere in the book; the remaining 55 photographs are either of objects or of sites taken from the ground). Its genesis was an exhibition (“Sicilia mai vista”) containing a wide-ranging selection of his work, not just archaeological, which was held at Modica between December 3, 2018 and January 6, 2019[12]. Sebastiano Tusa, then Assessore of the Cultural Patrimony of Sicily, visited the exhibition on its closing, and his very positive comments about the quality and importance of Nicosì’s photographs were reported in the press at the time[13]. Two months later, he tragically perished in the Ethiopian air disaster, and this book is the fulfilment of a wish that he cherished—to publish as a permanent record the archaeological photographs shown in that exhibition.

Despite having only an Italian title on the cover and the title page, the text of the book is in fact bilingual, with an English translation facing the Italian on every page. The text (apparently multi-authored[14]) is not a commentary on the photographs as such but a brief general summary of Sicilian archaeology (the Preface calls it a ‘Guide’), broadly arranged in chronological order. In that respect it differs from the book’s only predecessor, Sicilia dal cielo: le città antiche, now long out of print, and published in a somewhat smaller format, which contained largely site by site descriptions and had exclusive focus on the Greek and Roman cities[15]. In the new volume there are initially four chapters on prehistory, then two on the Sicans and the Elymians, and a short one on Greek colonization. Rather curiously one chapter is called “Sicans” and another “Sicans and Elymians”. The Siculi, while discussed in the former, did not succeed in getting into a chapter title. After that come three geographical sections describing individual sites in eastern, central and western Sicily. Chapters on “myth and destiny” and Roman Sicily follow, as well as a brief concluding envoi. Included also are bibliographical references (mostly to Italian works) and an index of places. The text is straightforward and for the most part uncontroversial[16]. There are passing references to the illustrations at appropriate places in the text, but no detailed explanation for the reader of what each photo actually shows. Occasionally there are mis-matches. The “most beautiful example of a city wall” (p. 73) at Naxos does not feature in fig. 34, which shows not “the sanctuary area” (so its caption) but rather two superimposed groups of houses and their accompanying streets, each with a different orientation and of a different period. The Preface gives a succinct summary of what follows in the text, but the present reviewer in particular cannot agree with the statement that “little is known about Sicily during the imperial age” (p. xv).

The great glory of the book is of course the 49 aerial photographs, most of them spread over two facing pages in a large format book (each page measures 302 mm by 239 mm, approximately 12 inches by 9.5 inches); only occasionally are critical details “lost” in the central spine of the double-page spread[17]. They cover 39 sites in all, some of them unfamiliar even to specialists (such as Mokarta: fig. 66). Another is the cover photograph, nowhere identified in the book: it features the remarkable Middle Bronze Age settlement of Faraglioni, together with its defences, on the tiny island of Ustica north of Palermo. All were taken in spring, so a few of the sites are pleasingly green with yellow flowers, before the heat of the Sicilian summer has taken its toll; the downside is that some (e.g. Eloro, Heraclea Minoa: figs. 44, 56) are rather overgrown at that time of the year, obscuring the visibility of the remains. Some images are particularly striking, like the spectacular shots of Monte Polizzello, Lipari, Akrai and the Syracuse Altar and amphitheatre (figs. 13, 30, 38 and 45). These are not the first published aerial photographs by Luigi Nifosì of ancient sites in Sicily: the new book can be seen as complementing a further 27 images, all different, which were published in 2008 in Above Sicily, further testimony to the outstanding talent of this photographer[18].

Sicilia archeologica vista dal cielo is, in short, a pleasure to handle, and a splendid feast for the eye. It is a fitting testament to the life and work of Sebastiano Tusa, who contributed so much to our knowledge of, as well as to the promotion of, Sicily’s rich archaeological patrimony, to which, had he lived, he would have contributed so much more.

Notes

[1] D. R. Wilson, Air Photo Interpretation for Archaeologists, London: Batsford 1982, 12, pl. 2 (taken 16th December 1925).

[2] Also in 1924 Crawford published under the aegis of his employer, the Ordnance Survey a pioneering first pamphlet, Air Survey and Archaeology (London: HMSO); a second edition was to appear in 1928.

[3] Wessex from the Air (Oxford: Clarendon Press 1928), available on line at https://archive.org/details/wessexfromair0000ogsc/page/268/mode/2up

[4] National Monuments Record (UK) TG2303/7 (CCC 2320) 20 JUL-1928; cf. S. S. Frere, Britannia 2 (1971), pl. I.

[5] A. Poidebard, La trace de Rome dans le désert de Syrie, Paris: Geuthner 1934. For a critique of Poidebard’s survey, not least his inaccuracies with site chronology, see D. Kennedy, “An analysis of Poidebard’s air survey over Syria”, in D. Kennedy (ed.), Into the Sun. Essays in Air Photography in Honour of Derrick Riley, Sheffield: Department of Archaeology and History, University of Sheffield 1989, 48–50.

[6] J. L. Baradez, Fossatum Africae, Paris: Arts et Métiers graphiques 1949.

[7] For Britain, France and Germany, major contributions were made by J. K. St Joseph, Roger Agache and Otto Braasch respectively. For Italy there is much of value in the pioneering work of J. Bradford, Ancient Landscapes, London: Bell 1957.

[8] R. V. Schoder S.J., Ancient Greece from the Air, London: Thames and Hudson 1974.

[9] G. Gerster and P. Cartledge, The Sites of Ancient Greece, London: Phaidon Press 2012; J. Nollé and H. Schwarz, Griechische Inseln: in Flugbildern von Georg Gerster, Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern 2007; M. K. Nollé and G. Gerster, Kreta: in Flugbildern von Georg Gerster, Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern 2009; G. Gerster and R.-B. Warkte, Flugbilder aus Syrien: von der Antike bis zur Moderne, Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern 2003; G. Gerster with D. Stronach and A. Mousavi (eds), Ancient Iran from the Air, Darmstadt, WBG/Philipp von Zabern 2012; and for a global survey, featuring 249 sites in 51 countries, G. Gerster and C. Trümpler, The Past from Above, London: Frances Lincoln 2005.

[10] E.g. A. Rieche, Das antike Italien aus der Luft, Bergisch Gladbach: Gustav Lübbe 1978 (including five Sicilian sites); W. Sölter (ed.), Das römische Germanien aus der Luft, Bergisch Gladbach: Gustav Lübbe 1981; D. Kennedy and R. Bewley, Ancient Jordan from the Air, Amman: Council for British Research in the Levant 2004; S. W. E. Blum, F. Schweizer, R. Aslan and H. Öge, Luftbilder aniker Landschaften und Stätten der Türkei, Mainz am Rhein: Philipp von Zabern 2006; A. Islami and Z. Hasani, Albania from the Air. Cultural Heritage, Tirana: Grid Cartels/Dolonja 2025; D. R. Abram, Aerial Atlas of Ancient Britain, London: Thames and Hudson 2022.

[11] Schoder (note 8), 11.

[12] E.g. https://www.bonajuto.it/magazine/sicilia-isola-mai-vista/

[13] https://www.ragusanews.com/tusa-le-foto-aeree-di-nifosi-specchio-di-una-sicilia-inedita/ e.g. “Non si pensi che le foto di Luigi Nifosì siano solo spettacolari da un punto di vista tecnico, ma sono importantissime da un punto di vista interpretativo. L’aerofotografia per scopi archeologici e culturali ci aiuta a percepire informazioni nuove, grazie alla sensibilità del fotografo. Grazie a questi scatti siamo in grado di comprendere le oscillazioni, attraverso i secoli, di brani significativi del territorio siciliano”. These comments are also reproduced in the book, pp. ix and (in English) p. xiii.

[14] The book is stated as being “edited” by the Fondazione Sebastiano Tusa, so the text was presumably a collaborative work by Valeria Li Vigni, its President, whose name appears on the cover, and Roberto Filloramo and Assia Kysnu Ingoglia, who are cited as “hanno collaborato” on the copyright page. Some passages were indeed written by Sebastiano Tusa: the account, for example, of the bronze statue of a dancing satyr from the waters off Mazara del Vallo (pp. 155–8) closely follows his paper in Sicilia Archeologica 101 (2003). The English translation of the book, clunky at times, is uncredited.

[15] E. Gabba and G. Giarrizzo (eds), Sicilia dal cielo: le città antiche (fotografie di Franco Barbagallo), Catania: Giuseppe Maimone Editore 1994, pp. 256.

[16] My main grumble is that the text at times has an old-fashioned ring about it, and does not always reflect the latest historical and archaeological scholarship. Not many today believe in a “Timoleontic revival” (p. 120) at Gela and Agrigento, for example, or that Segesta’s extramural temple was “built in a Elymian city for non-Greek cult and liturgy, so much so that it lacks a cella”, or that Roman control of Sicily “managed to drain resources from the island” (p. 115). The entry on Selinus (pp. 145–53) makes no mention of the NYU excavations on the acropolis or the long-running German campaigns which have revealed inter alia the agora, a sixth- and fifth-century BCE potters’ quarter, and Archaic defences which show that the original city was much larger than the visible one today. That for Segesta (p. 145) passes over in silence the Pisa excavations which have revealed so much about its late Hellenistic agora and its impressive, two-storey stoa. Morgantina’s agora and theatre are not “late fourth/early third century BCE” but belong to the Hieronian period, not earlier than 260 BCE (M. Bell, Morgantina Studies VII: the City Plan and Political Agora, Wiesbaden: Reichert Verlag 2022). Important excavations by Rome’s La Sapienza University of a major temple of Baal beside the so-called cothon, both clearly visible together with the circular temenos wall in fig. 179, surely also deserved a passing mention in the discussion of Motya (pp. 178–82). Of the three Imperial heads found at Pantelleria, the female one is identified as Antonia Minor on p. 225 but as Agrippina the Elder on p. 227 (and in the caption to fig. 97). I believe the former to be correct (Mouseion 17 [2020], 515–45).

[17] The aerial views of Heraclea Minoa (fig. 56) and the acropolis at Selinus (fig. 70) particularly suffer in this regard.

[18] L. Nifosì, Above Sicily (text by D. Fernandez), San Giovanni Lupatoto: Arsenale 2008, pp. 124–161 (there is a separate Italian edition, Il volo sulla Sicila, also 2008). Some of the sites there featured do not appear at all as aerial photographs in Sicilia archeologica vista dal cielo, such as the Roman villa near Piazza Armerina, Ispica and Cave di Cusa, as well as the “hellenistic-Roman” quarter and the ekklesiasterion at Agrigento. Other images, e.g. of Eloro and Heraclea Minoa (pp. 136–7), are clearer in that book than those of the same sites in the new one.