Adrienne Mayor excels at presenting the Greco-Roman world in ways that are creative, engaging, and irresistible. The revised edition of Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, and Scorpion Bombs is no exception. As she points out in the new preface, the volume, which outlines examples of biological, chemical, and unconventional warfare in antiquity, has influenced television shows, documentaries, museum exhibits, films, and even international summits on biosecurity. Mayor herself highlights the continued relevance and importance of the subject in a post-9/11 and post-COVID world, arguing that “one can only hope that a deeper understanding of toxic warfare’s mythic origins and earliest historic realities might help divert the drive to transform all nature into a deadly arsenal, redirecting it into the search for better ways to heal” (p. 288).

In the preface, Mayor points out that warfare in the ancient world was often far from fair or honorable, arguing that this is a sort of nostalgia projected back onto antiquity. Rather, she claims, “there never was a time innocent of biological warfare” and the “ethical concerns that surround [it]” (p. xiii). And this becomes the moral goal of this book: by understanding the long history of such questionable types of warfare, we in the contemporary world will learn from the past and continue to examine the questionable ethics and inherent dangers of biological and chemical weaponry. The introduction continues this theme with particular emphasis on the ubiquity and pervasiveness of unconventional warfare throughout time, throughout cultures, and throughout the world. And it is here that some problems arise in this book. Is the connection between past and present so direct? Are the motivations and modes of thought the same? Are the parallels with the past believable when we now live in a world of industrial warfare? Even Mayor recognizes these concerns, noting that many of the ancient stories she shares are not, strictly speaking, examples of biological or chemical warfare. Rather, she argues, they “represent the earliest evidence of the intentions, principles, and practices that evolved into modern biological and chemical warfare” (p. 8). Confronted with these challenges, she suggests “the need to expand the definitions of biological and chemical weaponry beyond narrow categories” (p. 8). This becomes a recurring challenge of this interesting and entertaining volume—definitions of chemical, biological, and unconventional warfare are somewhat fluid, examples do not always seem relevant, and claims of contemporary parallelism are often stretched. For instance, Mayor suggests the Biblical plagues in Egypt show an early intention to use biological warfare because the Jews prayed for such things to happen to their oppressors. She likewise argues that “the history of making war with biological weapons begins in mythology, in ancient oral traditions that preserved records of actual events and ideas of the era before the invention of written histories” (p. 22-23). Much as one might question how direct is the line between the modern and ancient worlds, just so one might question how closely myth reflects actual practice. Mayor asks the reader to accept these premises, when perhaps more nuance is required.

While these connections may be somewhat overstated, they do provide an interesting framework through which to understand our assumptions of antiquity and the ethics of our own time. This is reflected well in the first chapter, which uses the story of Heracles and the Hydra as indicative of the origins of biological weapons in antiquity and of ancient attitudes toward their use. In this chapter, Mayor tells the story of Heracles dipping his arrows in the venom of the Hydra. While mythological, Mayor contends that the stories of the arrows’ use in the Trojan War highlight the ancient debate between honorable and nefarious warfare. The black, festering wounds that the arrows cause also hint at an awareness in antiquity of the actual, physiological effects of a snakebite. The story of Philoctetes is particularly telling, as it provides a stark warning that the user of biological weapons is always at risk of becoming a victim, accidental or otherwise, of the very same weapons. This is the modern parallel and warning that Mayor draws with these myths, and, as she argues, such “weapons based on poisons, contagion, and combustibles are, of course, the prototypes of modern biological weapons and chemical incendiaries” (p. 48).

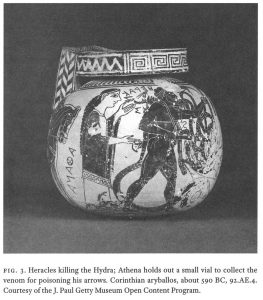

Chapter 2 moves b eyond myth into the more practical and scientific considerations of poisons and their antidotes. Here, Mayor raises another of her main arguments, namely that poisons were designed not only to inflict pain and death, but to cause terror. The fear of being struck with a poison arrow could cause more destruction than the arrows themselves. Much of this chapter focuses on types of poisons in antiquity, from hellebore and frogs to henbane and jellyfish. Mayor gives examples from many different cultures and time periods, and so there are times when stories and examples seem out of place or included only for their quirkiness. This does little to further her argument, but it does keep the reader engaged, entertained, and curious. This desire to draw connections and tell tales does at times lead to problems, however. For example, Mayor tells the story of the Scythians (whom she calls “biowarriors”) wearing a cup on their belts. The use of these cups is uncertain, but, since the Scythians also used poison arrows, Mayor suggests that these cups held the very poisons into which they dipped their arrows. As evidence for such a connection, she uses a vase painting that shows Heracles fighting the hydra. Behind the hero stands Athena. Mayor suggests that Athena is holding a small cup into which Heracles will place the venom he is collecting from the hydra. As she contends, “it is interesting that in early vase paintings…the goddess Athena is shown holding out a vial with a narrow opening to catch the venom” (p. 69). The only trouble is that the “vial” she is “holding” is not actually in her hand and is, in fact, the end of the scabbard for the sword with which Heracles is fighting the Hydra.

eyond myth into the more practical and scientific considerations of poisons and their antidotes. Here, Mayor raises another of her main arguments, namely that poisons were designed not only to inflict pain and death, but to cause terror. The fear of being struck with a poison arrow could cause more destruction than the arrows themselves. Much of this chapter focuses on types of poisons in antiquity, from hellebore and frogs to henbane and jellyfish. Mayor gives examples from many different cultures and time periods, and so there are times when stories and examples seem out of place or included only for their quirkiness. This does little to further her argument, but it does keep the reader engaged, entertained, and curious. This desire to draw connections and tell tales does at times lead to problems, however. For example, Mayor tells the story of the Scythians (whom she calls “biowarriors”) wearing a cup on their belts. The use of these cups is uncertain, but, since the Scythians also used poison arrows, Mayor suggests that these cups held the very poisons into which they dipped their arrows. As evidence for such a connection, she uses a vase painting that shows Heracles fighting the hydra. Behind the hero stands Athena. Mayor suggests that Athena is holding a small cup into which Heracles will place the venom he is collecting from the hydra. As she contends, “it is interesting that in early vase paintings…the goddess Athena is shown holding out a vial with a narrow opening to catch the venom” (p. 69). The only trouble is that the “vial” she is “holding” is not actually in her hand and is, in fact, the end of the scabbard for the sword with which Heracles is fighting the Hydra.

The next chapter shifts from weaponry to the poisoning and fouling of water as another unconventional tactic in warfare. Of particular interest are the “rules of engagement” that surround the use of such tactics. For an aggressor, the poisoning of water or the deliberate destruction of plants and animals was considered shameful and nefarious, while for the defenders such tactics were acceptable. Here again Mayor draws contemporary parallels in the rules of war, noting that modern governments claim to develop biological weapons for defensive purposes only. She then discusses the diseases caused by naturally unhealthy environments such as marshes and swamps, arguing that armies could deliberately compel their enemies to bivouac in these areas, thus causing outbreaks of plague. Whether this is truly a sort of “biological subterfuge” (p. 115) or simply a natural occurrence is not completely made clear, and our ancient sources are never quite so explicit; nevertheless, it is an intriguing interpretation of another way in which the terrain could be used as a tactical advantage.

Chapter 4 is perhaps the most conjectural and so most tenuous of the book. It focuses on the deliberate attempt to utilize plague as a weapon and uses as its starting point the 1344 CE siege of Kaffa by the Tatars. That this example is not from the ancient world highlights the challenge this chapter (and often this book) faces. Mayor draws overly strong connections between antiquity and the present, suggesting that Pandora’s Box or the Ark of the Covenant may represent plagues sealed in boxes, and she suggests that the storing of such “weapons” is similar to the contemporary need to store bioweapons in secure locations. At times, it seems that there is too much reliance on myth as proof of history. For instance, Mayor suggests that the plague sent by Apollo against the Achaeans in the Iliad is an example of the ancient use of bioweapons in war. She contends that a story like this “definitely reveals both the desire and the intention to wage what we now call germ warfare” (p. 127). This leap may be difficult for readers to make, and more proof is needed to suggest the ancients in fact thought in this way.

The fifth chapter discusses sabotage and subterfuge in war, recounting the story of Pompey’s army, which was once rendered ineffective by a “secret biological weapon” (p. 154), hallucinogenic honey. It is an interesting idea that ancient armies would use such means to gain an advantage over their adversaries, but whether it should be called a “biological weapon” is less clear. Once again, Mayor focuses on the terrifying effect even the fear of such assaults would bring, and she warns that tactics such as leaving poisoned wine behind for an invading army to discover would almost certainly cause collateral damage. These tactics, while perhaps effective, were indiscriminate, and, just as in antiquity, we in the contemporary world should consider all the inherent risks in such biological warfare.

Chapters six and seven are the longest in the book and examine the use of animals in war, especially for the spread of disease (chapter 6), and the use of chemical incendiaries (chapter 7). Both chapters incorporate a myriad of ancient examples to highlight the often unusual and gruesome ways in which ancient people fought war: pigs lit on fire to scare war elephants, beehives launched over city walls, fire ships sent against blockading fleets, and even ancient versions of napalm. As with most of this book, the stories are incredibly engaging and highlight episodes in ancient history that challenge the often idealistic ways in which contemporary audiences view the past. At times, some of these stories seem superfluous, an opportunity to tell another interesting anecdote; at other times, the examples become somewhat redundant. In the end, the chapters are engaging and fun, but could be streamlined a bit to flow more smoothly and be more focused.

The book concludes with an afterword that emphasizes the warning Mayor hopes to present to contemporary audiences: “a tragic myopia” (p. 280) afflicts those who choose to use biological or chemical weapons. In particular, Mayor focuses on the difficulty of disposing of such weapons and the dangers their storage will pose to future generations. How do we warn our descendants about these perils when they may not understand our language or our symbols? Much as the mythic stories of the ancient world teach us lessons today, she suggests that we must create our own stories to be passed down through the ages so that “the buried, indestructible Hydra’s heads of radioactive doom will remain undisturbed by human beings over time measured in eons” (285).

Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, and Scorpion Bombs is a page-turning and entertaining book, and many of the stories will be new and surprising for readers. It is not, without problems, however. The definition of “ancient world” is loose, and while Mayor attempts to draw examples from many cultures, it is clear the Greco-Roman world is the main emphasis (almost all images, for example, refer to Greco-Roman materials). The new maps and color plates do not add much to the work, and the use of images, as discussed above, is often questionable or superficial. For example, an image of a terracotta pig is used to support a claim that elephants might very well be afraid of burning pigs squealing and running at their feet. The image proves none of these claims. And finally, too many direct links or strong connections are drawn between the ancient world and the modern. The afterword helps to better understand the desire to draw these parallels, but too often the ancient and modern worlds are equated without the necessary nuance, and not always for the better. None of these concerns is disqualifying, and this book is a wonderful resource for anyone eager to learn more about this unexpected and often unexamined part of the ancient world, but it should be a starting point, not an authoritative source.

Greek Fire, Poison Arrows, and Scorpion Bombs is a page-turning and entertaining book, and many of the stories will be new and surprising for readers. It is not, without problems, however. The definition of “ancient world” is loose, and while Mayor attempts to draw examples from many cultures, it is clear the Greco-Roman world is the main emphasis (almost all images, for example, refer to Greco-Roman materials). The new maps and color plates do not add much to the work, and the use of images, as discussed above, is often questionable or superficial. For example, an image of a terracotta pig is used to support a claim that elephants might very well be afraid of burning pigs squealing and running at their feet. The image proves none of these claims. And finally, too many direct links or strong connections are drawn between the ancient world and the modern. The afterword helps to better understand the desire to draw these parallels, but too often the ancient and modern worlds are equated without the necessary nuance, and not always for the better. None of these concerns is disqualifying, and this book is a wonderful resource for anyone eager to learn more about this unexpected and often unexamined part of the ancient world, but it should be a starting point, not an authoritative source.