A review essay of Guido Petruccioli, Ancient Art and its Commerce in Early Twentieth-Century Europe: A Collection of Essays Written by the Participants of the John Marshall Archive Project. Oxford: Archaeopress, 2022. Pp. 312. ISBN 9781803272566.

This article is part of an occasional series on ethics and cultural heritage.

[Authors and titles are listed at the end of the review.]

“Said to be from Rome.” “Said to have come from Kataphygi, Attica.” “Said to be from Taranto.” When I first began to visit classical collections, I was mystified by this “said to be” construction, which appears on thousands of labels in the Metropolitan Museum, Boston Museum of Fine Arts, British Museum, and many other museums. How could an identification of an origin be so precise and yet so vague at same time? Did the phrasing indicate a curator’s considered but not absolutely certain theory? Or was it a claim tossed off by someone the curator didn’t trust at all? Above all, I wondered, who said it?

Thanks to the newly digitized archive of John Marshall, the Metropolitan Museum’s purchasing agent in Rome from 1906-1928, we can come closer to answering these questions for hundreds of the museum’s Greek and Roman artifacts. In this essay, I will describe the Marshall Archive and review Ancient Art and its Commerce in Early Twentieth-Century Europe (Archaeopress 2022, ed. Guido Petruccioli), a collection of essays that introduce and contextualize the archive. I also want to use this essay to argue that asking “who said it?” about a “said to be” provenance is not the silly question I convinced myself it was when I was a student. Instead, I believe all scholars should try to find out the most that they can about the acquisition history of artifacts they study. I will give examples of how such information from the Marshall Archive has brought me to a new understanding of some artifacts in the Met, both helping me to do better scholarship and avoid bad scholarship. I will conclude by calling for museums to offer such information more readily – because while the Marshall Archive reveals much new information about the Met’s collections, what it makes most clear is just how much information remains hidden.

Puppy in Rome

Marshall (1862-1928) was the son of a wine merchant from Liverpool. He met the wealthy Bostonian Edward Perry Warren in 1881, when they were both undergraduates at Oxford. As Stephen Dyson points out in the excellent biographical chapter he contributed to the edited volume, they were both outsiders there: Warren as an American and Marshall as someone who had not gone to one of the great public schools and whose family was “in trade.” Upon graduation, Marshall took a position as Warren’s secretary, accompanying him on buying trips in the 1890s as Warren began to accumulate a collection of antiquities, partly for himself and partly on behalf of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. (His prize possession was the Warren Cup.)

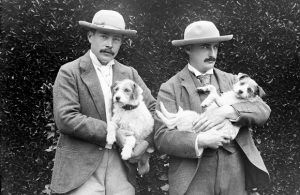

A photograph from 1895 shows Marshall and Warren posing with matching suits, hats, and mustaches, cradling matching small dogs. (Fig. 1) They spent long periods living together at Lewes House, Warren’s residence in England, and called each other “Puppy” in the many letters they wrote each other when apart.[1] Warren published defenses of “Uranian love” and intended Lewes House to be a refuge for his circle of intellectual homosexual friends. Marshall and Warren were certainly partners, but whether lovers at all or lastingly is, as is usually true of relationships in the period, unclear. In 1908, Marshall married Warren’s cousin, a woman in her early 50s. She died in 1925, and both Warren and Marshall in 1928. The three are buried together in a cemetery in Tuscany.

Working with Warren gave Marshall the opportunity to develop his eye for ancient art, practice detecting forgeries, learn the complexities of ownership and export laws that shaped the market, and take his place within its network of dealers, agents, and potential customers. Most importantly, Marshall met the American scholar Edward Robinson when they were both visiting antiquities collections in Munich in the early 1890s.

In 1905, Robinson became an antiquities curator and assistant director at the Met, ultimately serving as its director from 1910-1931. Robinson was determined to build the Met’s classical art collection. When he arrived, this consisted of many artifacts from Cyprus, nearly 700 plaster casts, and not much else. In 1906, Robinson hired both Marshall, as purchasing agent, and Gisela Richter, who would curate the museum’s classical department until 1948. Robinson also turned a large portion of the museum’s acquisition budget to antiquities. The Classical Department spent, for example, $45,000 on acquisitions in 1917, $94,000 in 1923, and $185,000 in 1926.[2] This material filled a new wing, which opened in 1925 and still holds the museum’s Greek and Roman collections.

Marshall was buying for a museum with both funds and space to form a major collection. He lived in Rome and made frequent trips to Paris and Athens, and was thus perfectly positioned to take advantage of the most active marketplaces for antiquities in a period when rising prosperity and the desire to modernize meant that antiquities were relatively frequently uncovered during construction projects. This period also saw the solidification of national antiquities ownership laws, meaning that Marshall had to adjust his strategies to acquire antiquities that Italy and Greece were increasingly reluctant to permit to leave the country. Marshall’s archive is an invaluable resource for understanding not only the formation of the Met’s collection, but also broader topics including the history of American taste for antiquities and debates about cultural heritage protection. It also provides some of the best surviving evidence for how he and other purchasers in the period broke or skirted laws intended to protect antiquities – and thus raises questions of what, if anything, we should do about these antiquities now that we have a better understanding of how they left their countries of origin.

Marshall left 1,674 photographs and associated notes about who offered the object to him, when, what price they asked, and what, if anything, they said about where the artifact had been found, to the British School at Rome. Hundreds of his drafts and copies of letters and telegrams passed to Warren, who gave them to the Bodleian Libraries at Oxford. The members of the John Marshall Archive Project have worked since 2013 to digitize these items and create a free online archive. The project has also transcribed the documents, explained their labyrinth of variant spellings and abbreviations, linked documents dealing with the same object together, and made them searchable by keywords including dealer and museum names. When known, the entries indicate which museum currently holds the artifact; although most are in the Met, the archive also includes artifacts ultimately acquired by other museums, including the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts, Art Institute of Chicago, Cleveland Museum of Art, and Berlin’s Altes Museum.

Marshall did not maintain a complete record of all his transactions. Rather, the archive is a selection of the objects he purchased or was offered. For example, the archive preserves no information about Marshall’s most notorious purchases for the Met, the forged “Etruscan Warriors,” although it does reveal that he purchased at least four other artifacts now in the Met from the forgers Amadeo and Teodora Riccardi, including the vases in the shape of helmeted heads that they used as models for one of the warriors.

The more I use the archive, the greater my appreciation for the care that has gone into creating and structuring it. The same is true of the accompanying volume, edited by Guido Petruccioli. The book introduces readers to Marshall, framing him and his activity within social, legal, and scholarly historical contexts. Readers will emerge well-prepared to engage with the Marshall Archive for their own research, but many chapters are valuable stand-alone contributions, including Francesca de Tomasi’s examination of the complex network of laws and regulations that governed the Italian antiquities market at the turn of the century (Chapter 10) and Vinnie Nørskov’s wide-ranging discussion of the use of different types of photography, from casual snapshots to painstakingly staged studio photographs, by collectors and scholars during the period (Chapter 3).

A substantial portion of the volume consists of chapters discussing the objects in the archive by material. Beryl Barr-Sharrar’s chapter on the bronzes serves as a useful discussion of the Met’s holdings, since the museum has not published a catalog of these since 1915. Nørskov also contributes a chapter on the vases and terracottas. Roberto Cobianchi covers the rather rag-tag bunch of paintings and other non-antique objects in which Marshall only occasionally dealt. Nearly half of the objects included in the archive are marbles; these are examined in two chapters, with Petruccioli looking at Greek sculptures and Susan Walker at the Roman portraits.

Taken together, the contributions of Petruccioli (Introduction and Chapter 9) and Mette Moltesen (Chapter 2) provide a crucial overview of the network of participants in the antiquities market of the early 20th century. The Met was just one of the well-funded collections competing for antiquities at the time, and Marshall’s archive is filled with correspondence with (and about) the men who acted as agents for these rival collections. Marshall seems to have appreciated their expertise, and probably wanted to keep cordial relationships in the relatively small expat community of Rome. They include Wolfgang Helbig, who bought for Carl Jacobsen’s Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, and Paul Arndt, who acted for Munich’s Glyptotek, as well as Jacob Hirsch, Paul Hartwig, and Ludwig Pollak.

Marshall seems to have only infrequently purchased from those who actually dug up antiquities, preferring instead to work with established dealers. These included the owner of a gallery in Palermo whose brother, a priest, smuggled ancient coins over the border to Switzerland by hiding them inside his cassock, and the Jandolo family, who staged large sculptures in a cavern dug into the Capitoline Hill, which is where Marshall first saw the famed Old Market Woman. (Fig. 2)

The Old Market Woman is one of the examples given by the volume’s contributors of how the archive’s laconic documents can be developed into vivid pictures of the acquisition of particular artifacts. de Tomasi untangles the history of this sculpture, which was discovered by chance during a construction project in Rome in 1907 and arrived in New York in 1909. The Jandolos paid 26,000 lire for the sculpture and quickly sold it to Marshall for 36,000 lire. When the Met made its new acquisition public, Italian authorities investigated how it left the country, since export permits were reserved for only commonplace antiquities. Ultimately, the authorities concluded that they had failed to notify the landowners that they were not permitted to sell it. Marshall wrote to Robinson several times to report on the trouble, detailing the contortions the Jandolos went through to try to disguise their involvement. But his tone was unworried. A lawyer had assured him that the Met had no legal liability for any laws the Jandolos may have broken. “What lies Jandolo tells are not my concern but his,” Marshall concluded.

Such insulation likely explains why Marshall worked with dealers rather than diggers. Documents in the archive show that Marshall generally paid dealers a lump sum for an artifact and its shipment, which included obtaining an export license.[3] Marshall does not seem to have been terribly concerned to verify whether dealers actually obtained this license. It was not his concern if a dealer instead bribed customs officials or paid a smuggler to get an artifact out of Italy. Marshall worked with dealers he could trust to offer refunds if something went wrong, whether the seizure of an artifact or its rejection by Robinson and Richter as a forgery or otherwise unacceptable. These benefits counterbalanced the premium the dealers were able to charge as middlemen, such as the 10,000 lire profit the Jandolos made on the Old Market Woman (around $64,000 today).

The contributors to the volume concentrate on the Italian material, but the Marshall Archive also offers some hints towards reconstructing the network of Greek antiquities dealers with shops in Athens or Paris or both who were active in the first two decades of the 20th century. Marshall cultivated an extensive network in Greece, beginning on his first visit (nearly four months in 1896-97) and continuing with a number of subsequent trips and what seems to have been an extensive correspondence. This information sheds light on what has been an understudied area, since Yannis Galanakis’ valuable work on Greek dealers stops in the late 19th century.[4] Fortunately, these dealers are easier to trace once they are recorded from the later 1920s on in the archives of the Brummer Galleries, which are more comprehensive and detailed than the Marshall Archive and are also freely available online. I recommend the Marshall and Brummer Archives for researchers interested in the dealings of Michel L. Kambanis (often spelled Kampanes by Marshall), Georges Yanacoupolos, Nicholas Roussos, E.P. Triantaphyllos, C.A. (Kostas) Lembessis, and Theodoros A. Zoumpoulakis (whose name appears in a frustrating multitude of transliterations and misspellings in various sources; at the Met he is alternately Zoumpoulakis or Zoumboulakis).

Three Heads are Better than One

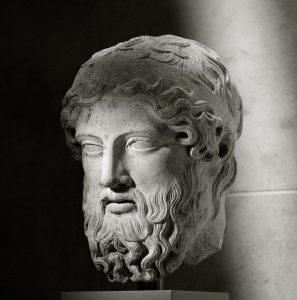

When we find an artifact in the Marshall Archive, like this Roman head of Zeus, we can guess that it was Marshall who passed on information to the Met that ultimately resulted in its label reading “said to be from Rome.” Of course, nothing about this is simple, as Petruccioli’s painstaking reconstruction of the negotiations for the purchase of this head shows. It is worth spending some time considering this example in order to think more clearly about what a “said to be from” provenance can reveal – and what it can conceal.

An otherwise unknown dealer named Mariani offered three Roman heads to Helbig, hoping he would purchase them for the Ny Carlsberg Glyptotek, but Carl Jacobsen, the museum’s choosy founder and funder, turned them down. The dealer Alessandro Jandolo, acting as an intermediary for Mariani, then showed the three heads to Marshall. Marshall kept photographs of all three in his archive, revealing that one was a head of Zeus-Ammon and the two others nearly identical “Albani”-type Zeus heads, although one was in slightly worse condition.

Petruccioli convincingly argues that Marshall saw the value of Roman sculpture primarily as a source for information about High Classical Greek style, and thus had little interest in the later style of the Zeus-Ammon head. Although the twin Zeus heads were probably a pendant pair, Marshall was equally uninterested in evidence about how the Romans used sculpture. Thus, he decided to purchase only the better preserved of the pair, recording in his notes for November 1913 that he bought it “from Mariani 15000 with permit” – that is, the 15,000 lire also paid for the dealer to procure an export permit. Marshall also records that after this sale the dealer Elio Jandolo “[a]ssured me that the fine head bought from Alessandro Jandolo came, as did the Boston Homer, from near Porta Portese.”

What to make of all this? The Porta Portese gate stands just a few yards from the Tiber River, whose embankments were being constructed at the turn of the century. The excavations necessary for this work meant that “found near the Tiber” is a common claim for antiquities sales of the period. Petruccioli points out that Marshall often passed on to the Met what sellers had told him, but everyone understood that these sellers had ample reason to lie about findspots, whether to avoid scrutiny by the authorities or simply to conceal their sources from rival dealers.[5] The “Boston Homer” is mostly probably a head of Homer procured by Warren in 1904 for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, which currently describes it as “possibly acquired in Rome.”[6] Marshall kept a photograph of the Boston Homer in his archive. While the Met’s Zeus is currently described as a 1st–2nd century CE Roman copy of a Greek marble herm of ca. 450–425 BCE, the Homer is dated to the late 1st century BCE or 1st century CE.

While it is certainly possible that all four heads came from a single Roman deposit uncovered by chance during construction on the Tiber embankments, it is equally if not more plausible that they were found somewhere else and that the Boston Homer has nothing to do with the three Mariani heads. It seems that the Met’s label, “said to be from Rome,” was arrived at by downgrading Jandolo’s more specific claim of “from near Porta Portese.”

Elizabeth Marlowe has argued that antiquities without a secure archaeological find-spot present intractable epistemological limitations to scholars regardless of when they resurfaced.[7] She has specifically criticized the false aura of certainty of “said to be” descriptions, especially those that make no attempt to indicate by whom the claim was made or in what context.[8] Marlowe for full descriptions of all available evidence as well as the reasoning process behind attributions of date and place.

The case of the Mariani heads proves the value of this approach. The Met presents its head without any indication of its association with the other two, even though this information is far more reliable, and more interesting to current scholarship, than any of the speculation that went into the “said to be” description. This is all the more true since the current location of the two heads Marshall did not buy is unknown; the photographs in his archive might be their only surviving record. The Met’s label might thus read read “purchased in Rome” and include information about the other heads.

To be fair, I do not know what exactly Marshall told the Met about the Zeus; it is possible that Richter was never aware of the other heads. I emailed the Met’s Onassis Library for Hellenic and Roman Art to ask for access to the department’s archival records on Marshall’s purchases broadly, as well as to ask a few more detailed questions that the materials in the Marshall Archive raise but do not answer, but have so far received no reply.

Fragmented Finds

In other cases, Richter was certainly aware of find-spot information offered by Marshall, but this information is nevertheless either difficult or impossible to discover from the museum’s public records. For example, more than 30 small terracotta, bronze, and bone artifacts with sequential acquisition numbers (11.212.16-53) are labeled as “said to be from Taranto.” Richter much more specifically described the artifacts as “the contents of three tombs from Tarentum” in a 1912 publication, writing that their “chief interest” was in the “fair idea of the regular tomb furniture” of the 3rd century BCE they could give.[9]

It was Marshall who purchased these artifacts (for 7,000 francs in 1911). If his specific information about their origin was good enough for Richter, what reason is there to downgrade the certainty with a “said to be” label now? And although most (but not all) of this group is displayed together, it is difficult to understand their relationship unless you visit the museum. Only one of the artifacts (a bone doll) has a public record that notes its association with all the others. The other artifacts either give a vaguer indication of relation or simply fail to note any relationship to other objects at all.

In other cases, subsequent events have revealed that a find was fragmented before Marshall saw it. Long-running scholarly discussion about how fragments from the same Greek painted vases ended up in the hands of different collectors has recently attracted more public attention. Nørskov shows that dealers were manipulating these fragments as long ago as 1908, when Marshall wrote to Robinson to say he had just been offered more pieces of a cup he had purchased the year before, including a fragment containing the signature, which confirmed the attribution to Hieron. Marshall pledged that he would “not pay outrageously” for these new fragments, but noted that he would “have to pay pretty well in order to secure any other pieces which may turn up.” Marshall told Robinson that the new pieces had “been just found,” but we can guess that a canny dealer would see the benefit of reserving the signature for a future purchase. That dealers were also increasing their profits by dividing up fragmentary vessels and selling different parts to different collectors is shown by a cup signed by Euphronios as potter and attributed to Onesimos. Pieces first arrived at the Met in 1912, with further fragments, undoubtedly sold to another collector at that time, donated in 1971 and 1972.[10]

Megakles… Maybe

Before I conclude with some wider-ranging thoughts on doing scholarship with “said to be” antiquities, I want to lay out a detailed final example: an archaic Greek grave stele carved with a youth and a girl. (Fig. 3) The Met calls it “the most complete grave monument of its type to have survived from the Archaic period,” since it retains substantial portions of the carved shaft, a palmate acroterion topped with a sphinx, and pieces of a base. This base is carved with a fragmentary inscription, translated on the museum’s online object record as “to dear Me[gakles], on his death, his father with his dear mother set [me] up as a monument.”[11] This webpage also comments that

Some scholars have restored the name of the youth in the inscription as Megakles, a name associated with the powerful clan of the Alkmeonidai, who opposed the tyrant Peisistratos during most of the second half of the sixth century B.C.

This stele is not discussed in the volume; the following thoughts are my own, based on photographs and over twenty associated texts in the Marshall Archive and elsewhere. I want to especially consider two aspects of the Met’s presentation of the stele. First is the fact that the Met labels the stele as “said to be from Kataphygi in Attica, southeast of Hymettos.”[12] Second is the amplification of two letters in the inscription into a full name, Megakles—with the suggestion that this is not just any Megakles, but a particular known historical figure.

Coming to an understanding of how trustworthy these claims might be requires close attention to the information in the Marshall Archive. The stele presents a unique case, since Marshall owned it before he took his position with the museum. He thus preserved an unusual number of the documents generated during his negotiations with the Met, a process that stretched over several years.

It was Warren who first bought the largest portions of the stele, although Marshall does not indicate when—only that Warren gave him a half-share ownership of the piece in 1903 and transferred it entirely to him in either 1908 or 1909. Marshall bought more pieces of the shaft and inscription in 1900, 1904, 1905, and 1906. In an undated letter to Friedrich Hauser, Marshall sketches the fragment of the inscription he then possessed (a chunk of the middles of the second and third lines) as well as two more that he had just seen, but not purchased: the first part of the first line and another piece of the second and third lines. Presumably shortly thereafter, in a letter dated August 29, 1907 to the Greek dealer Jean P. Lambros, Marshall writes that he is sending a photograph and “begging you to find what you can of the missing pieces.” This letter to Lambros also describes a fourth fragment either seen or owned by Marshall, of three letters probably from the second line.

So, by 1907, Marshall knew that the first line began “μνε͂μα φίλοι με…” and that, from the alignment and length of the fragments of the second and third lines, the missing piece of this first line could have held around eight more letters. Marshall, as he would later describe to Robinson, had at some point begun to believe that the person who set up the monument (not its dedicatee) was “the great Megacles, father in-law of Pisistratos and great grand-father, wasn’t he, of Pericles.” Wanting to confirm this, Marshall offered his Greek sources either £10 a letter for any additional fragments or £500 for the rest of the inscription; that is, around $2,000 today for a letter or $100,000 for all. (The texts in the Marshall Archive cannot answer the question of whether Marshall assigned these bounties only after he saw the additional pieces in 1907 or if these pieces were brought to him precisely because he had already been offering rewards.)

These were substantial amounts, on top of the around £2,500 Marshall and Warren had already spent on pieces of the monument. But Marshall believed this investment would be amply rewarded. In 1909, when Robinson asked if he would consider selling to the Met, Marshall quoted a price of £8,500. Marshall wrote that he knew this was “a big sum,” since a stele like it would sell for no more than £5,000 if it lacked an inscription. But Marshall emphasized the connection with Megakles and assured Robinson “I know exactly where it was found and where almost all the remaining fragments are likely to be found.” Marshall pledged that the price would include any further pieces he could find in the next year, during which he already planned to go to Greece “and to finish up the matter which only needed a couple of spades and a little sense.”

After some competition with the German curator Theodor Wiegand, who knew the stele from a visit to Lewes House and wanted it for Berlin because in 1903 the Antikensammlung had purchased a segment of it (with the girl’s head and hand), the Met paid Marshall £8,000 (around $1 million today) in 1911. This price was to include any further fragments he could buy for up to £500.[13]

Robinson published the new acquisition in the museum bulletin for 1913, explaining that the reconstructed base included “two pieces of the inscription,” while a “third piece, containing the first two words and part of a third, was discovered some years ago, but has since disappeared. By great luck, however, a paper impression of it which was taken before its disappearance has come into our possession, and a plaster cast made from this has been inserted in its place in our restoration of the block.”[14] Comparing the photograph in this publication with Marshall’s 1907 sketches, it seems that Marshall kept a squeeze of the first line, but hadn’t bothered to do so for the other, smaller piece he had inspected at the same time.

Today, the monument includes five pieces of the inscription, all in marble. (Fig. 4) I am fairly certain that it was these missing pieces, seen by Marshall in 1907, which were purchased by Walter Cummings Baker in 1951 from the dealer Theodore Zoumboulakis and then donated to the Met, but the Met has not responded to my attempt to confirm this.

Frustratingly, the documents in the Marshall archive do not reveal from whom he or Warren purchased any of these pieces with the exception of a 1913 transaction, in which Marshall paid £480 to E. P. Triantaphyllos for further fragments of the carving on the stele.[15] The Met’s object record does not mention Triantaphyllos, but does include the information that a piece of the youth’s shoulder and arm were purchased from M.L. Kambanis in 1922—although without specifying who at the museum acted as the purchaser, and whether the sale happened at Kambanis’s gallery in Athens or the one in Paris. Marshall visited Athens in that year, and regularly bought from Kambanis, and so Marshall was probably the purchaser.[16]

The 1913 purchase from Triantaphyllos is particularly important because, as Marshall wrote to Robinson, Triantaphyllos claimed that the stele “was found 33 Hodos Herakleidon—a street of Hodos Peiraios, about 300 metres past the gas works, going off over the railway toward the Theseion.”[17] This is presumably 33 Iraklidon Street, a five-minute walk from the Temple of Hephaestus (formerly called the Theseion).

But by 1925, when Marshall visited Wiegand in Berlin, he had changed his mind about the stele’s origins. According to Wiegand’s notes from the conversation, which are preserved in archives in Berlin, Marshall claimed that the stele had been found in the area of Anavyssos, at the same spot as the archaic female figure known as the Berlin Goddess.[18] Marshall seems to have been offered the Berlin Goddess in 1923. He turned it down, but retained this new information about its claimed association with the Megakles stele.

I found one final description of the findspot in Richter’s 1928 publication of the monument in Antike Denkmäler. Without describing the source of her information, she writes:

The stele is said to have been found in the vicinity of Athens. While the surface of the upper portion is well preserved, with numerous color traces extant, that of the lower half of the figures is much weathered. This difference in preservation is due to the circumstance that the monument was apparently broken up in Greek times, and the fragments used to line other graves, except with the large piece containing the legs of the youth and the body of the girl, which remained lying on the ground face upward and so was exposed to the weather.[19]

We can now return to my two points. The first (how did the museum come to describe the monument as “said to be from Kataphygi in Attica, southeast of Hymettos”) remains an unanswerable question. Marshall said either a specific address in Athens or Anavyssos.[20] Richter said “in the vicinity of Athens.” Anavyssos is south of Hymettos, and the whole area could be regarded as the vicinity of Athens if we use a rather generous range of 30 or so miles. But is “Kataphygi” a further specification of what was said by Marshall and Richter, or a substitute piece of information provided by someone else? On what basis was one or the other (or both) of Marshall’s find-spots disregarded? Neither the source nor the content of the information about Kataphygi is revealed.[21]

Just as I would not use a piece of information I found only in an anonymous book without any citations, no matter how much I trusted the publisher, so, too, does it strike me as ridiculous to depend on this information about Kataphygi without any ability to judge its probability for myself just because it is put forth by the Met.

Regardless of where, exactly, the monument was dug up, Greek law should have banned its export.[22] By that time, Greece had declared that newly excavated antiquities belonged to the state and that only unexceptional, “surplus” antiquities could be exported. (Once an antiquity left the country, it seems that Greece sought its repatriation in this period only when someone confessed to excavating or smuggling it, which led, for example, to the seizure of the Anavyssos Kouros in Paris after it had been smuggled out of Greece in 1932.[23])

Let us turn to my second point, about the reliability of the association of the stele with the name and/or historical person of Megakles. The first hurdle, it seems to me, is one that the museum does not mention at all: does this inscribed base pertain to this stele? While Richter’s statement about the monument being found in pieces in other graves does help provide an explanation for why it took so long to accumulate the various sections, this piecemeal excavation means that the fragments of the stele and the fragments of the base were brought together rather than found together.[24] We must ask if we trust whomever it was who first associated stele and base.

The two sections are in different materials (the base is poros and stele a finer marble), which is common for the period. The surviving pieces of the base are now encased in a reconstructed rectangle into which the stele’s shaft is inserted. (Fig. 5) We cannot see whether the inner faces of the base fragments line up with the slot that holds the shaft. However, only one of the surviving portions lines up with the slot on the surface; the others end before it begins. It seems possible that these fragments once belonged to a base for another monument with entirely different dimensions. But the question of whether or not the inner portions of the fragments correspond with the inserted stele is one only Met staff can answer. Currently, I cannot see much reason for associating the base with the shaft other than that Marshall was told they belonged together by the dealer(s) he bought them from.

There is also the issue of Marshall offering large rewards for more of the inscription. It is disturbing to think of “a couple of spades” at work in the post-Archaic cemetery described by Richter, digging up an unknown but probably large number of graves in search of those that used bits of this particular stele. But isn’t it also possible that someone thought of claiming the reward by making the missing pieces? Kambanis and Lambros were dealers, but were also respected scholars on ancient Greek numismatics, among other matters. They would have been capable of composing an inscription. And in 1935, Stanley Casson pointed out in AJA that the lettering on this inscription was different from that of other 6th century examples.[25] Instead of carving the circular letters freehand, as the others did, this carver had laboriously tapped a vertically-held chisel hundreds of times to peck out a circle. (Fig. 6)

Read with a skeptical eye, the Marshall Archive reveals the existence of the means, motive, and opportunity for forgery—whether this might be a new creation of the inscription (or portions of it) or simply the false association of stele and inscription. The archive provides a big warning: we must do more research before we can interpret the stele by means of the inscription or read the inscription as if it pertained to a stele with a figure who might bear a name beginning with “Me” (or even read the word as a name at all).

“Inaccessible to Outside Researchers”

In his essay about the ethical problems of publishing unprovenanced inscriptions that have only recently appeared on the antiquities market, Brent Nongbri notes that these problems are “different, though still related” to the problems posed by working with “manuscripts that were acquired much earlier in the twentieth century but almost certainly in violation of Egyptian laws that regulated the export of artifacts at the time.” When I began reading Ancient Art and its Commerce in Early Twentieth-Century Europe, I planned to write a review addressing just such problems. But now, having gotten some sense of the icebergs of hidden information sometimes connected to a visible “said to be” label, I no longer think it is worth much to speculate about the ethics of working with such artifacts when I have no idea what information is being concealed – or what state of affairs my publications might be helping to normalize and perpetuate. But while I do not yet have an answer to ethical questions, my foray into the Marshall Archive has made it obvious that investigating the circumstances of the acquisition of antiquities can be immensely valuable to scholarship itself. As I hope I have demonstrated in this review, such information can expand our understanding of museum objects in some cases and provide valuable cautions in others.

But although Marshall acquired hundreds of classical artifacts for the Met, his name appears in the provenance of only a handful of artifacts on the museum’s online database. And while the Marshall Archive goes a long way to illuminating the histories of many of his other acquisitions, it is incomplete. It contains Marshall’s copies or drafts of only some of the many letters he sent to the Met. The museum surely has many of the complete letters in its files, along with other information important to making both scholarly and ethical determinations about the artifacts. For example, these files should show which artifacts came with export permits and which did not.

Marshall’s records are not the only ones held by the Met that I would like to see. The museum has restricted the availability of a number of Brummer Gallery records that deal with their own antiquities purchases. And while the Met holds both the personal and private papers of Gisela Richter, when I enquired in 2015 about the possibility of accessing them to write a biography, the staffer who responded told me these papers “are currently unprocessed and inaccessible to outside researchers.” “I will certainly contact you” when they became available, the staffer assured me, but I have heard nothing since—not even when I asked again while writing this essay.[26]

It is true that I have been rather a critic of the Met’s collecting practices, and they might regard letting me at their archives as the equivalent of the Spartan boy opening his cloak to the fox cub. Others probably will receive a better welcome, and more information, than I. But I would argue that information available only upon request is of much less value than an open archive whose users can determine what questions they want to ask as they explore.

Making more information about the early formation of their antiquities collection publicly available would demand substantial time and funding – scarce commodities in any museum. The current impossibility or difficulties in accessing information about the Met’s acquisition of antiquities in the early 20th century could well be due simply to the Greek and Roman Department, and the museum as a whole, having many other priorities when allocating budget and staff time.

However, the Met has recently stated that it holds a “responsibility to be transparent about the works in our collection and what we know about the objects” and so “we are continually publishing images and the known ownership history for all works in our online collection.” It has also announced that it will hire a team of provenance researchers to focus on potentially looted artifacts. I hope these initiatives will include making public records from Marshall, Brummer, Richter, and others involved in the formation of the Met’s antiquities collections. We will learn much about these artifacts. Then, we can begin to debate ethics.

Table of Contents

Chapter 1 John Marshall – A Biographical Essay – Stephen Dyson

Chapter 2 Collectors and the Agents of Ancient Art in Rome – Mette Moltesen

Chapter 3 The Photographs in John Marshall’s Archive – Vinnie Nørskov

Chapter 4 John Marshall, The Met and the Historiography of ‘Greek Sculpture’ – Guido Petruccioli

Chapter 5 Faces in Stone: A Case Study of Marble Portrait Sculptures of Roman Date Purchased by The Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York via John Marshall – Susan Walker

Chapter 6 The Bronzes in the John Marshall Archive – Beryl Barr-Sharrar

Chapter 7 John Marshall’s Dealings with Vases and Terracottas – Vinnie Nørskov

Chapter 8 ‘Non-antique’ Objects in the John Marshall Archive – Roberto Cobianchi

Chapter 9 John Marshall’s Trading Network – Guido Petruccioli

Chapter 10 Cultural Heritage Preservation during John Marshall’s Time: The Export of Antiquities from the Unification of Italy to the 1909 Law – Francesca de Tomasi

Notes

[1] E.g., “There is a limit to purchases; Puppy must not overspend”: Letter from Marshall to Warren, June 11, 1892, quoted in Osbert Burdett and E. H. Goddard, Edward Perry Warren: The Biography of a Connoisseur (1941): 169.

[2] Calvin Tomkins, Merchants and Masterpieces: The Story of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (1970): 124.

[3] Earlier in his career, when Marshall was helping Warren buy artifacts for the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, his letters indicate that he was more directly involved in exportation. One letter records a variety of plans for making antiquities seem less valuable than they were, in order to ease their passage through Italian customs. Marshall writes that he would “doctor” a vase signed by Polygnotus by “painting the name out with something that will wash off.” He also discusses hiring “a rogue” recommended by Helbig to “put through the Customs for about a hundred lire” an artifact vaguely referred to as “the Eleusinian.” Marshall reports that the same man “got the Copenhagen busts out of Rome for almost nothing when Tyskiewicz was in despair as to how he could pass them” by covering “the noses and chins and ears with stucco as though they had been repaired, and made them look so bad that the authorities thought them valueless.” Letter from Marshall to Warren, June 11, 1892, quoted in Edward Perry Warren: The Biography of a Connoisseur, 170-71. Interestingly, the only vase related to Polygnotus that came to Boston through Warren is an unsigned stamnos (MFA 95.21) now attributed to the circle of Polygnotus. Perhaps Marshall doctored it but forgot to tell anyone to uncover the signature?

[4] E.g., Yannis Galanakis, “An Unpublished Stirrup Jar from Athens and the 1871-1872 Private Cxcavations in the Outer Kerameikos,” Annual of the British School at Athens 106 (2011): 167–200.

[5] Warren summarized this confusion in a paper about the life of an antiquities collector he read to the trustees of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1900, stating that a collector “daily weighs lie against lie to elicit the truth.” Edward Perry Warren: The Biography of a Connoisseur, 339.

[6] The Boston Museum of Fine Arts curator Phoebe Segal has offered a considered appraisal of the value of this type of label wording in “‘Said to be from’: Best Practices for Using Unscientific Findspot Information,” in Collecting and Collectors from Antiquity to Modernity, ed. Alexandra Carpino, Tiziana D’Angelo, Maya Muratov, and David Saunders (2018).

[7] Elizabeth Marlowe, Shaky Ground: Context, Connoisseurship and the History of Roman Art (2013).

[8] Elizabeth Marlowe, “What We Talk About When We Talk About Provenance: A Response to Chippindale and Gill,” International Journal of Cultural Property 23, no. 3 (2016): 217-236.

[9] Gisela Richter, “Department of Classical Art: Recent Accessions,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 7, no. 5 (1912): 93–98.

[10] The Met’s online catalog describes the 1971 acquisition as an anonymous gift, while the 1972 donation is attributed to E.D. Blake Vermeule, who is the daughter of Cornelius Clarkson Vermeule III, a noted antiquities collector and curator at the Boston Museum of Fine Arts. Since she was in elementary school at the time, we can guess that likely both donations came from her father, who regularly used pseudonyms when donating art, as when he presented artifacts to the British Museum in the name of his dog, Sir Northwold Nuffler.

[11] Μνε͂μα φίλοι με[c. 8]

πατὲρ ἐπέθεκε θανόντ[ι]

χσὺν δὲ φίλε μέτερ ( vac. )

This is rendered as “To the dead Philo and Me[…] the father erected (this) monument, and together the dear mother…” in its most recent museum publication: Seán Hemingway, How to Read Greek Sculpture (2021), 69.

[12] The online record for the monument reads “said to have come from Kataphygi, Attica,” but the fuller language is used for the gallery labels and also appears in Hemingway.

[13] Apparently the Met balked at the price in 1909. Discussions resumed in 1911, when Marshall, about to enter a London hospital for surgery, and with two sisters to provide for (his younger brother was apparently driving their father’s inherited wine business into the ground), decided he should sell the stele. Robinson wrote that he was still interested but had to persuade others at the Met. Meanwhile, Wiegand heard from Warren that Marshall was contemplating selling and offered £8,000. Marshall sent off a telegram to Robinson, telling him he had 24 hours to match the price if the Met wanted the stele. On November 15, 1911, Robinson replied “MetMusArt takes Megacles 8000.” But on December 2, he clarified that a museum committee must approve the deal before it was final. Finally, on December 20, 1911, Robinson cabled that the purchase was confirmed.

[14] Edward Robinson, “An Archaic Greek Grave Monument,” The Metropolitan Museum of Art Bulletin 8, no. 5 (1913): 94–99.

[15] Seth Estrin (University of Chicago) kindly pointed out to me shortly after the publication of this essay that this 1913 transaction with Triantaphyllos almost certainly had nothing to do with the Megakles stele, but instead was Marshall purchasing another Archaic stele, Metropolitan Museum of Art 12.158. Thus, the find spot near the Temple of Hephaestus is not relevant to the Megakles stele. I leave my error in the body of the text as an example of the type of confusion that would be remedied by access to Marshall’s complete letters in the museum’s files in place of the selected and sometimes fragmentary notes in his own archive. [Footnote added on 31 May 2023.]

[16] The Met acquired several more pieces after Marshall’s death. The sphinx was purchased from an unnamed English private collection in two parts in 1936 and 1938; Richter records that a dealer showed her a photograph and she guessed that the sphinx for sale, missing three of its paws entirely and most of the fourth, might fit on top of the stele, which bore three paws and part of a fourth. Richter also noted that several fragments belonging to the youth’s body were identified in the study collection of the National Museum of Athens by Semni Karouzou in 1966 and G. Despinis in 1967; plaster casts of these, along with the piece of the girl in Berlin, are currently inserted into the monument. Gisela Richter, “The Department of Greek and Roman Art: Triumphs and Tribulations,” Metropolitan Museum Journal 3 (1970): 73–95.

[17] Wolf-Dieter Heilmeyer and Wolfgang Massmann, Die ‘Berliner Göttin’: Schicksale einer archaischen Frauenstatue in Antike und Neuzeit (2014), 21.

[18] See footnote 15. [Footnote added on 31 May 2023.]

[19] Gisela Richter, “Archaic Grave Stele in the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York,” Antike Denkmäler IV (1928): 33-40, 33. The Met’s page for the monument lists 39 publications that reference the work, including ten by Richter, but this article is not among them.

[20] See footnote 15. [Footnote added on 31 May 2023.]

[21] On May 26, 2023, two days after the publication of this essay, Onassis Library staff responded to my inquiry to state that the Kataphygi findspot is “based upon information in the Marshall records that are not yet processed and, therefore, not available to outside researchers.” This response adds to rather than decreases my questions. Did this claim come before or after Marshall’s other claims about the monument’s findspot? On what information was Marshall basing this claim? Why has the museum decided it is the most credible? I remain convinced of the need for transparency. As I believe that restrictions on the availability of such information are often imposed by the highest levels of museum administration, I also want to make it clear that I am grateful to Onassis Library staff for providing me with the information they are permitted to disclose. [Footnote added on 31 May 2023.]

[22] Daphne Voudouri, “Law and the Politics of the Past: Legal Protection of Cultural Heritage in Greece,” International Journal of Cultural Property 17, no. 3 (2010): 547-568.

[23] Elizabeth Pierce Blegen, “New Items from Athens,” American Journal of Archaeology 41, no. 4 (1937): 623-628, 632.

[24] It could also be true that all the pieces were found at once, or much closer together in time, and that a canny dealer was parceling them out gradually to get a higher total price. But I think a gradual discovery is more likely, both because Richter is correct that the very different preservation levels on different pieces indicated different depositions, and because Marshall is right that a sale of all the pieces together would have brought much more than the separate pieces; the rarity is in the ensemble.

[25] Stanley Casson, “Early Greek Inscriptions on Metal: Some Notes,” American Journal of Archaeology, 39, no. 4 (1935): 510–17.

[26] On May 26, 2023, two days after the publication of this essay, Onassis Library staff responded to my inquiry to confirm that Richter’s papers “are not fully processed” and thus are not available to outside researchers. [Footnote added on 31 May 2023.]