With contributions by Carla Benocci and Valter Proietti; translated by Gary P. Vos

This lovingly fashioned and lavishly illustrated volume (especially in the review copy hb.) represents Müller’s supplementation and repolish of his 1994 monograph, including inter alia documents and specs accessed since that enquiry, plus frequent visits to Vatican and Villa, and powered by disappointment if not dudgeon at lack of positive response, now remedied by detailed demolition of dissenting scholarship of the interim. (English translation from Dutch is acceptable quality.) I have some good news for him: I for one (still) agree with his identification of the scene as a ‘free’ post-Euripidean Hippolytus-Phaedra visualization, though I’m far more of a besotted devotee than he allows himself to be.[1]

The front cover does the traditional obeisance of using Panini to star the [non-]Wedding as centrepiece of Roma Antica, diffusing its special kinda blue all over the shop (as also in its mosaicked-up room in the Vatican), choosing the version with the tourist/connoisseur with guidebook in hand (rather than the painter/restorer/recreator with palette or the dignitary commanding the entire Imaginary Gallery). Of course the youth who takes the knee to stare straight into the picture models engaged response, tells us to soak up what you see—though he conveniently blocks and sidelines the skulduggery and female toplessness that engrosses the tourist’s sidekick to left, in favour of the golden boy with his knee in the way plus the cerulean ring of decorous women to right… So whereas Müller takes a proudly and effectively iconological approach, diligently seeking out and picking over forerunners, cousins, parallels for the schemata there to be recognized in the mural’s individual figures, groups, and ensemble/s, and rightly demonstrates that this picture-strip is no inert hand-me-down replica but an eclectic composition, I yet feel there’s a strain of Gombrich’s ‘dictionary fallacy’ about the procedure practised.

The front cover does the traditional obeisance of using Panini to star the [non-]Wedding as centrepiece of Roma Antica, diffusing its special kinda blue all over the shop (as also in its mosaicked-up room in the Vatican), choosing the version with the tourist/connoisseur with guidebook in hand (rather than the painter/restorer/recreator with palette or the dignitary commanding the entire Imaginary Gallery). Of course the youth who takes the knee to stare straight into the picture models engaged response, tells us to soak up what you see—though he conveniently blocks and sidelines the skulduggery and female toplessness that engrosses the tourist’s sidekick to left, in favour of the golden boy with his knee in the way plus the cerulean ring of decorous women to right… So whereas Müller takes a proudly and effectively iconological approach, diligently seeking out and picking over forerunners, cousins, parallels for the schemata there to be recognized in the mural’s individual figures, groups, and ensemble/s, and rightly demonstrates that this picture-strip is no inert hand-me-down replica but an eclectic composition, I yet feel there’s a strain of Gombrich’s ‘dictionary fallacy’ about the procedure practised.

Importantly Müller nails the lasting, likely permanent, influence of the initial, pre-archaeological, pre-Pompeian, C17th take on the Wedding as precious visual link between us and the Realien of Antiquity as documented in classical texts, though he prudently mutes the continuing incentive for both Aldobrandini-Vatican and Humanist mainstream purposes to guard the visit inside the cutaway ‘bedroom’ for holy matrimony. Discovery of Roman fresco work—the contemporary ‘blue Apollo’ with phallic lyre of the Palatine House of Augustus (‘by the same workshop and perhaps even by the same painter’ as AW (p.134) ?

Not really) and the whole Villa Farnesina livery added to our arsenal of Bay of Naples murals more than vindicates identification of AW as (a) ‘mythological painting’. But what we—that deictic inset and I—are really hot for is ‘mythological painting‘. From which viewpaint, Müller’s persuasive nomination of Hippolytus-let’s call it-Phaedra launches what should be an endlessly rewarding plunge into intermediality, as discoursing recursively between mythic narrative matrix, textual dramatization, visual re-realisation, and their cultural histories. And, yes, of course envisioned myth never can cut entirely loose from ‘realities’, including not least, in this signal instance, nuptials.

AW‘s room in the Vatican museum is there, along with Pompeian syntagms such as Medea-Phaedra-[Paris-and-]Helen in the House of Jason,[2] to underline how much ambient semiosis we’re missing, quite apart from what’s lost from the fragmentary picture itself. But Müller’s bombshell is to assure us that the frayed architectural pattern below the picture shows a garland stretching to left from the capital, revealed when the frame that made AW a ‘painting’ was removed, plus ‘minimal but undeniable’ evidence of ‘the nail that affixed’ a second—matching…?—garland ‘to the wall’ stretching to right (p. 29 n.12). This should indicate that the fresco, cut out to left from a corner of its original room, once extended to twice its present width of 2.42m. Could the call to imagine lift off from here, and guess that what starts to the right of the masonry wall and ‘threshold’ straddled by ‘Hippolytus’, a weathered, much-repainted, and variously intuited background that Müller painstakingly shows once regaled us with a great outdoors, was scheduled to lead, through his devoted habitat—hunting territory—off toward the light of window or door onto a garden prospect and the outside? Müller reveals that, like the ‘architrave’ re-painted to head the scene rather than mark its abuttal on ‘the entire wall system’ (p.43), the vertical line on the right edge is part of a restorer’s re-framing of the ‘painting’, and that early reports witness a (second) tripod/brazier/altar (?) to the right of what remains, before presumed trimming to fit installation up high, framed and soon shuttered, in AW‘s purpose-built loggetta at Villa Aldobrandini.

Appendices give us the 1620s de Peiresc letter recording the 1601 find-spot, circumstances and first description of AW, itself ‘dug up’ in 1993; and a detailed history (by Carla Benocci) of the Villa loggetta (with a ‘modern developments’ addendum by Valter Proietti). We don’t hear too much about how the Aldobrandini Pope, Clement VIII, took time out (e.g. from making sure Giordano Bruno was burnt at the stake) to buy the Quirinal site for building the Villa, kept in the family by gift to nephew Cardinal Pietro A., just as Carmelite monks on the Esquiline happened to hit on AW‘s buried room, underground down their garden path—more or less instantly shorn of a grapevine surround and assigned its Roman wedding ritual status (as in the Vatican blurb ‘… consoles the bride in the throes of virginal anxiety, before the arrival of her husband…’). But we do get a full chapter pursuing the ascribability of AW to the horti Maecenatiani palace built in the 30s bce. and its chances of proximity to the newly assembling court. The balance of pages are devoted to scotching rival/dissident scholarship, not least the efforts to pin fresco to text from Catullus 61 on down, Winckelmann’s bid for Peleus and Thetis, among others’ others, and a feature Appendix pouring scorn on claims to find sundry classical ‘Brautbilder’—without then looking to exploit the range of representations for comparison and contrast. Whereas, relatedness within difference is what must make AW talk through other images, mythological and/or whatnot, to its viewers. Of course women in Antiquity were never just wives, but they were never far from modifying the association, and painted women were never less real for being mythical.

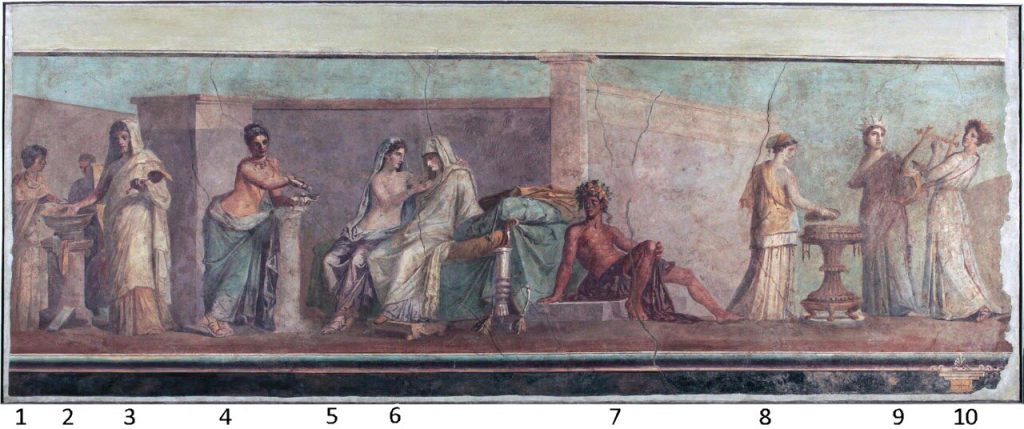

The meat of the book, however, comes in the reinforced ‘New Interpretation’ chapter, where we tune in to the Pompeian idiom of the wall and pilasters, and the schematic figures 4, 5 (Aphrodite), 7, 9, 10 (from left); 3 must be ‘maid’ because flabellifera; 6 Phaedra fevered/deranged/kaluptomenê and 7 Hippolytus stephanephoros; 9 heavily reworked Artemis [minus archery but] in [now? weird] corona radiata, with nymph attendants; 4 (Aphrodite’s sidekick: Peitho?) links together Aphrodite’s triple assault on Phaedra, with 3 as Euripides’ Nurse, with her assistants 1-2. Müller summons up a plausible tripod/brazier/altar for sacrifice and trophies for Artemis, © Hippolytus, and imagines a spirited hunt awaiting him off to right. Which is where we would be coming in.

Euripides had statues of Aphrodite and Artemis bracketing the stage and likely suggesting movement from former to latter; he could not show the bedroom; his confrontational shattering of ‘the myth’ into competing versions appeared on the same stage but sequentially; his text(s?) featured trajectory and metatextual conclusion; his writing played constitutively between speaking and silence, veiling and revealing, healing and poisoning, shame and aggression, to self- and/or other; was reified in props, especially the killer letter. The fresco sets us up to begin, one goddess visibly active, the other waiting her turn, not yet incensed. The massive wall divider between 1-3 and 4…6 counterposes the resources brought out into play from the hidden stores of the house, preparing to treat Phaedra, cool her down, with a potion and get her talking, but Aphrodite’s aphrodisiac will instead turn this into fanning the flames, visually metaphorizing the come-on (and get him) that Aphrodite pours into bewitched Phaedra’s ear, whether by charming the stepson or by damning the both of them with her pharmacological letter-to-be-penned. Nurse-maga-goddess, they get Phaedra, overpower, possess and may even become, unpack as her, 3+1+1-in-1 making, visualizing, the 5 into figure 6. Whereas, also without a sound, Hippolytus is there but not there, a semi-attached/-detached ‘sticker’ standing proud of the dutiful/abandoned females advancing stepmother’s way and/or his way, the interior that he shields from but all the same turns towards, while he just about keeps a toehold in the enclosed ring of aloof serene static removed non-compliant female world beyond the—his, their—imploding home.

The tragedy may play the couple‘s not meeting as/vs meeting through writing; the picture hands us potential for writing (in the closed diptychon between 1 and 3),the play administers poetry/song, always distancing us from but delivering us to living, whether ‘now’ as the celebration of Artemis that will get Aphrodite’s goat as she monopolizes the Hippolytuses of this world (don’t even look, male precant viewer) or as envisioning Euripides’ play/s or any way ‘the myth’ could tell on/implode/sanction sexual taboos/bait at the edge of exogamy: in our extant Euripides, the end will sing of Artemis promising revenge on Aphrodite’s next chosen one and instituting the ‘rite and song’ that ‘brides-to-be shall hereafter cut their hair in Hippolytus’ honour … and when young girls sing songs, they will not forget him, his name will not be left unmentioned, nor Phaedra’s © for him stay unsung’ (vv. 1423-30).[3]

See: that staring second wife can’t speak for shame, yet, on stage because deliriously uninterpretable, so far, but she’s shipping the message; and see (we can’t): that altar trimmed away to right has a future we can’t hear but must imagine—and of course this seductive/horrific mural has, precisely, Wedding stroked but splashed, all over it.

To get stoked up over the AW you need to zone in, but thank Müller for zooming in to whereabouts we are.

Notes

[1] Like Wikipedia, poised halfway close to agreement, Eelco Kappe: https://www.tripimprover.com/blog/aldobrandini-wedding.

[2] Bettina Bergmann (1996), ‘The Pregnant Moment: Tragic Wives in the Roman Interior’, in Natalie Boymel Kampen (ed.) Sexuality in Ancient Art: Near East, Egypt, Greece, and Italy, Cambridge University Press: 199-218, esp. pp. 202-207, in Room E.

[3] Barbara Goff (2007), The Noose of Words: Readings of Desire, Violence and Language in Euripides’ Hippolytos, Cambridge University Press: chapter 5, ”The End’, esp. pp. 112.