(The author of the following review, in collusion with the hard-copy editor of BMCR [for they are both ‘Graeculos homines, contentionis cupidiores quam veritatis’: Cic. de or. 1.11.47], has contrived this review in a most charming and, at the moment, unelectrifiable way to confound the electronic editor by including reproductions of Edward Lear drawings illustrating each of the Xerxes verses quoted. The electronic editor takes such chaffing in good spirits, confident that the electron is mightier than the pen; for the meantime, e-readers of BMCR will have to exercise their imaginations!

Note added 23 August 2001: O fortunati ambo, colluders past, that the ineluctable march of the electrons has brought us to the happy day when BMCR is able to, ut nostrates aiunt, retrofit this classic review, now almost a decade old, with electronic avatars of the illustrations that once graced only our paper edition.)

Edward Lear (1812-1888), the least loved of his parents’ twenty-one children, sketched the watercolor of Delphi that adorns the dust jacket of Evans’ new book on Herodotus. Epileptic Lear had to draw to support himself from age fifteen. His precocious skill at picturing parrots seems to have been matched by his subsequent interest in dangerous climes, including Albania, Greece, Palestine, and Turkey. The charm of his more than two thousand romantic drawings, “Dirty Landscapes” (as he whimsically called them), the Greek ones executed on three different extended visits between 1848 and 1864, draws many Hellenophiles to museums in Cambridge, Massachusetts and Athens. He covered on foot much of the ground that the Great King of Kings traversed in his invasion of Greece, including the canal across the Athos peninsula. He was also a lonely poet of genius, in the nonsense vein. His zany sketches match well his exuberant poetry. He wanted an appointment from the King of Greece as “Lord High Bosh and Nonsense Producer.” He composed variations on the theme of Xerxes, a remarkably useful, nearly essential resource for the tail end of your nonsense alphabet. Noake’s charming biography remarks (141) that no other X appears in his alphabets. I share Evans’ regard for the Victorian artist and I hope that the editors of this unsolemn journal will permit me to quote and illustrate examples. If readers are lucky, perhaps the High Editorial Command will reproduce in the rarer, hard print form of their welcome, different creation, the pleasant portraits of the Great King from the hand of Lear, once drawing master to the equally Great Queen Victoria (1846).

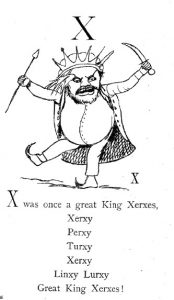

X was once a great king Xerxes,

Xerxy

Perxy

Turxy

Xerxy Linxy Lurxy Great King Xerxes!

This is not great poetry or insight, but rather an example of how the joy of words can seduce anyone from the quest for meaning. This may happen to sober historians as well as to griots and literate poets. I suggest my reader declaim these verses at full voice at home and in the office.

I.

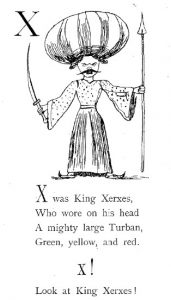

X was King Xerxes

Who wore on his head

A mighty large turban,

Green, yellow, and red.

X !

Look at King Xerxes!

Here we find hectic visual imagination accoutered in anachronistic clothing. Gaudy garments in fact are essential elements to Aeschylus’ portrait of Xerxes and Herodotus. They tinge our last pathetic glimpse of that bedevilled despot in the story of Artaynte and Amestris’ robe of many colors (9.108-13).

Evans’ “Three Essays” recapitulates over thirty years of valuable research and publication on elements of Herodotus’ peculiar invention, history. The compact volume first discusses imperialism, particularly Asiatic. Although Evans acknowledges a debt to Fornara’s (1971) insight that the Peloponnesian War was “the catalyst that animated” (7) Herodotus’ enterprise of investigating the earlier conflict, the idea is not here further developed. Rather Evans discusses the conceptual modes by which imperialism is presented: revenge, nomos, guilt/blame, Fate. Croesus’ unique reference to the kyklos tôn anthropeiôn prêgmatôn is not here given undue significance (see 87, 144). Evans concludes that human choices, and their consequences, not divine puppeteering, explain events in the Histories (35). Rather than gullible, Herodotus can be shown to be shrewd and cynical about imperialism, the dynamics of expansionist policies, and the “illness that attacked mature empires” (21, 28, 65). Evans’ unrigorous essays never calculate the number or frequency of the verbal or conceptual patterns that he has observed. Phrases like “it needs little imagination,” “more than possible,” “documented well enough,” “Herodotus makes more than the occasional obeisance” (all on p. 33 in five consecutive lines) are frustratingly vague and unsatisfactory. The essay form does not invite quantification.

II.

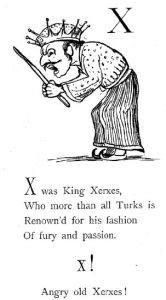

X was King Xerxes,

Who more than all Turks is

Renown’d for his fashion

Of fury and Passion.

X!

Angry old Xerxes!

Evans’ second essay shows that Herodotus’ portrait is more nuanced than this. Xerxes there is also magnanimous, some what insecure and immature. Lear’s reference to “Turks” may be excused gratia similiter desinentis.

The middle essay treats individuals in the Histories specifically Croesus, Cyrus, Darius, unsound Xerxes, opportunistic Mardonius, Themistocles, and Pausanias, with side-lights on Miltiades, an individual not quite a hero, and Leonidas, a hero not quite an individual (74). We learn that personae need to be “historicallly credible,” that the Asiatics are sketched “to fit a cycle of history,” that the two Greeks extensively treated have been portrayed as “typical of the[ir] states” (42, 86, 88). Similarly, the main Cyrus logos was chosen “to portray the sort of king who started the Persian Empire” (56). These quotations would lead the experienced reader to expect a radical critique of Herodotus’s historical value, but Evans does not in this chapter address this question, pro or contra but seems to assume an essential facticity for events, persons, descriptions. It’s somewhat puzzling to those who combat the Fehling syndrome.

III.

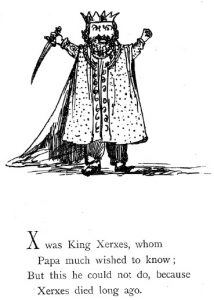

X was King Xerxes, whom

Papa much wished to know;

But this he could not do, because

Xerxes died long ago.

Here Lear’s father shows an interest, which Evans’ second essay shares, in the biography of ancient heavyweights, and Lear, again like Evans, expresses awareness of the fragility of accurate tradition, assuming it ever exists. This topic is explored in the final essay.

Evans begins the last and longest essay, “Oral tradition in Herodotus,” by considering the date of publication, degree of ultima manus for the text, partisanship or patronage (none discovered—except for desire to gain maximum exposure and a crowd-pleasing aim to entertain; 49, 95, 130), and the ancient author’s murky c.v. Evans assumes many (partial?) oral performances by Herodotus, either bardic, often repeated recitations or public readings from his papyrus rolls.[1] This chapter offers less familiar ideas, so my remarks concentrate on it.

Comparisons are drawn to the Manding and Bambara griots, “a type of minstrel belonging to an endogamous caste-like group” (Goody 1987: 101). These men, often praise-poets, listen, learn, modify their praise-epics and legends until “the right version” for their paying audiences shapes up through hundreds of performances: “The remembrancer creates the past that he professes to relate” (97). Evans’ Herodotus travels the performance circuit—Delphi, Olympia, Panathenaic games in Attica—”where an author might set up his booth and an audience would gather,” “possibly even, like the aoidoi, wearing special costumes” (99 and n.56, 130). Evans admits that the only evidence for Herodotus’ historical recitals is late (Plutarch, Dio Chrysostom, Lucian, Vita Marc. of Thucydides, the patriarch Photios, the Suda), their possible ceremonial function at a panegyris unclear. We observe the risk here of explaining obscura per obscuriora.

Evans well displays the traces in the Histories of “audience reaction,” loci where doubters and scoffers are remarked (or imagined: 1.193.4, 3.80.1, 6.43.3). He perhaps overinterprets the first-person plural verbs to include presumed auditors: “we know x or y”, or “the Danube is the largest river we know” does not nearly prove oral performance, much less composition (101). Legein ta legomena here is described as a defensive tactic to ward off live audience criticism.

Evans does not address Fehling’s provocative thesis that all Herodotus’ source citations are the “obvious” ones, data is too conveniently divided among sources, “party bias” is never disregarded, epichoric confirmations are too neat and never diverge within each group. In a word or so, the charge is “total invention.” As I have discovered for myself, it is a hard hypothesis to argue with except on a house-to-house, case by case campaign. For a model of such a refutation of Armayor’s arguments, see Evans himself (1991b) or Pritchett. But many of Evans’ concepts dovetail more with the Novelist Herodotus than the Historian Herodotus, so his more conventional conclusions surprise. Having read both careful and nearly irrelevant reviews of my own study of this seductive author, I sympathize with any author’s plaint that s/he should be reviewed for what s/he does, not what s/he never intended to do. I have been chastised for not proving the factuality of each fact that Herodotus relates. With all respect for Evans’ unusual erudition and careful generalizations, I offer several sometimes critical but always well-intentioned comments. Writing a review becomes more problematical when one has published on the same topics, a fact rarely recognized even in review journals. We might benefit from essays reviewing comparatively reviewers’ reviews: metareviewing, we might dub it.

Herodotus’ sources (107-13) include monuments, a few public records in Greece, logopoioi (writers), and most importantly, logioi (oral “remembrancers”). Here Evans includes purveyors of both oral tradition and part-oral, part-monumental, part-written traditions, such as respectable Egyptian temple secretaries. Evans presents substantive support for this frequently attacked Egyptian logos to oppose the doubts of Armayor and Fehling; see pp. 134-41. He plays down the always obscure (and therefore tempting to magnify) Hecataean element in Herodotus. He envisions Herodotus determining local tradition from accounts of trained specialists (the logioi). Then he “collated, verified, and amplified them by cross-checking” in a very modern manner which sounds right to me (110, 124). One sub-chapter is entitled “Herodotus as Field Worker.” Sometimes epichoric traditions of different communities could be interlinked into one story as well as compared, sometimes separate communities were asked for their story of a tale in which others had mentioned them.

In this latter case, the “invisible hand” nudged the collector towards an evaluation of truth in the marketplace of the reported past. An account “became true” by outlasting others, by being told without further contradiction. This reconstruction seems optimistic (or cynical) to me, as a way to attain historical truth. Thucydides lodged more than one complaint about uncritical ancient audiences (1.20.1, 3; 1.21-22; 6.54.1), and Herodotus often enough has a bone to pick with opinio communis, when there is one.

His general exclusion of mythology results from his method of consulting the available logioi, “specialists who claimed to have a coherent purview of the past” (ix). Thus Herodotus wrote up an account that reflects their often different parochial versions, taking care meanwhile to meet the Hellenic public’s criteria of credible, coherent, exotic, and enjoyable. On the other hand, Herodotus was “constrained by the canon of historical accuracy,” a small bore weapon in this epoch, we surmise (64, where found? whose? how known? when previously had this taxonomy of knowledge appeared?)

Evans valuably discusses the (un-)reliability of African oral traditions. Lists (and Herodotus provides many) seem unnatural to purely oral cultures and their versions wobble badly over the years (113, 118-19). Goody denies the concept of history to pre-literate cultures (1968: 27). Different tradition-rememberers, some self-supporting (jeeli), some official (baba elegun), some paid house-retainers (awlube; Goody 1987: 102)[2] work differently (Yoruba, Rwanda, Ashanti, Kuba , Bobangi, e.g.). Thereby they support different models for the historiographer seeking modern analogues. Which type of memorialist, however, if any, fits “oligoliterate” archaic and early classical Greece? But (or and) the Hellas of Herodotus in 425 BCE was already “a largely written culture” (95). Spartan historical exploit-performers at the syssitia are possible, but unattested. The Platonic Hippias Major 285 D (not B) emphasizes Spartan delight in the legendary past, genealogies of heroes, founders of cities (pasê hê archaiologia), not recent history, as Evans realizes (125).

Evans analogizes too easily from both the stature and treatment of ancient poets and modern sub-Saharan nonliterate “living archives.” The Africanist and Oralist Jack Goody argues (1987: 78-109) that even the Iliad has been strongly affected by the existence of writing. When we turn to later Greek prose and historia, something very different, the gap can only be greater. Before writing, social digestion and elimination alter “facts,” especially (but not only) when societies are rearranged. “Structural amnesia” affects what has now become irrelevant (Goody 1968: 33). Evans hedges his claims in proper scholarly fashion (131), but the thrust remains that illiterate African wandering tradition-tellers, looking for favors, money, and food, supply a fruitful means of understanding Herodotus’ immense, fixed, well organized prose text. Jacoby’s work on Greek epichoric literature seems underutilized, e.g., his comments on historical consciousness (1909: 98; 1949: 201). The Greeks tolerated no orthodoxy, challenged all myths, divine and legendary. Herodotus’ story is full of contradictory accounts, weighted and presented at the suitable moment.

Evans recognizes Herodotus’ quantum leap forward in exploring alien cultures, comparing local traditions, and producing historical analysis. He was not just retailing what he heard (131).

Here Herodotus remains the honest recorder, open-minded but cunning with his human sources, serious in his research and his travels, preoccupied with explaining the vicissitudes of empires (144). But the image of him putting together “a mosaic of epichoric traditions of unequal value” (132) contains a metaphor that implies a pre-existent historical coherence or image that may mislead. The events (or some of them) occurred; the participants and their descendants gave them meaning(s); Herodotus rejected some, accepted some, found—from his own unique perspective—new, deeper meanings in the junkyard of data and interpretation he assembled.[3]

This book quotes some transliterated Greek phrases but eschews Greek type. The absence implies (assuming money did not determine the situation) an audience of literary theorists or classical civilization students rather than ancient historians and philologists. Rezeptionskritik demands attention to the issue of Evans’ intended readers. The first two essays will seem sound, if hardly novel, to experienced students of historiography. Several stories are retold more than once (e.g., 4.136-42, 9.89, 9.122). The third essay offers useful summary of contemporary oral poetics and the nature of African tradition-tellers, but their applicability to any ancient Greek prose-writer, especially to Herodotus, in an age of increasing documentation, seems highly speculative. Rather little is made of early European ethnographers of the Americas. The dust jacket blurb led me to hope to learn more of the eighteenth-century Fr. J.-F. Lafitau. In this case we have a traveller from another culture recording and evaluating the customs of a differently structured society. The parallels might be more enlightening, yet more depressing.

Insofar as Evans articulates a hypothesis of oral composition generally aired casually and without exploration of consequences, his essay permits real debate and evaluation. Like Fehling,[4] Evans presents a challenge to those of us who still consider Herodotus to be a historian in our sense, not an immensely clever and intensely lazy novelist or an analogue to illiterate African record-keepers. Unlike Fehling, Evans does not draw the radical, uncomfortable, logical conclusions about the historicity of the Histories that some of his ideas would seem to require.

A good bibliography and a serviceable index of subjects (not locorum) complement a handsomely produced volume with footnotes graciously appearing at the foot of the page.[5] There are telling asides, such as “Mardonius was a special breed: an ‘unwise adviser'” (70), understated corrections to opiniones paene communes such as Herodotus’ position as Alcmaeonid quasi house-historian or “patsy” for Athenian propaganda about Spartans (84). Certain sections echo Evans’ earlier book (1982): “the nature of oral tradition” entitles parts of both; the same individuals (but more) are chosen for study of characterization.

APPENDIX

The Excellent Double-extra XX

imbibing King Xerxes, who lived a

long while ago.

REFERENCES

ARMAYOR, O.K., 1985. Herodotus’ Autopsy of the Fayoum (Amsterdam).

EVANS, J.A.S., 1982. Herodotus. Twayne’s World Authors Series (Boston).

EVANS, J.A.S., 1991b. “The Faiyum and the lake of Moeris,”AHB 5.3: 66-74.

FEHLING, D., 1989. Herodotus and his ‘Sources’, tr. by J. Howie (Preferred by the author to the original German of 1971).

FORNARA, CH., 1971. Herodotus (Oxford).

GOODY, J.R. & and WATT, I., 1968. “The consequences of literacy,” in Literacy in Traditional Societies, ed. J. Goody (Cambridge), pp. 27-68.

GOODY, J.R., 1987. “Africa, Greece and oral poetry,” in The Interface Between the Written and the Oral (Cambridge), pp. 78-109.

JACOBY, FELIX, 1909. “Über die Entwicklung der griechischen Historiographie,”Klio 9: 80-123.

JACOBY, FELIX, 1949. Atthis (Oxford).

JACKSON, H., 1947. The Complete Nonsense of Edward Lear (Repr. 1951, New York).

LATEINER, D., 1989. The Historical Method of Herodotus (Toronto). Soon to be available in paperback [unpaid advertisement]. NOAKE, V., 1968. Edward Lear. The Life of a Wanderer (New York). PRITCHETT, W.K., 1982. “Some recent critiques of the veracity of Herodotus,” in Studies in Ancient Greek Topography IV (Berkeley and Los Angeles), pp. 234-285.

[1] His publication late in life of his researches was intended to take advantage of a burgeoning book trade (145). It was not exactly an after thought, but a new, unexpected economic media opportunity. On such reasoning the first monumental and comprehensive work of Western prose (and non-fictional) literature saw the light of day almost accidentally.

[2] To avoid misrepresentation, I herewith state that I know nothing of African tradition-tellers beyond what Evans and Goody have taught me.

[3] So too Evans’ view of an “excursive style” with many digressions implies a standard of clear origin. There has never been evident agreement, beyond rare examples labelled by Herodotus (4.30.1, 1.171.1), as to what constitutes divagation from the main path, or indeed, what is that path. More important, there was no previous paradigm to which one might conform.

[4] Fehling (247-49, 254) pooh-poohs the survival of oral traditions through centuries. His Herodotus stayed at home all his life at the desk, wrote pseudo-history, invented nearly everything, creating facts, speeches, and the sources themselves (243-45).

[5] Printing errors are few: read khresmologos for kresmologos (12, 76), Momigliano in the Bibliography, Levi-Strauss with an accent in the Index, italicize a title (139 n.203), correct the date of Grene’s translation to 1987 (27 n 69).